|

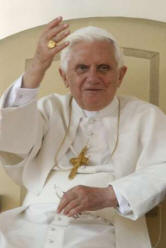

Pope Benedict XVI- General Audiences |

General

Audience

General

Audience

On St. Bonaventure

"All His Thought Was Profoundly Christocentric"

H.H. Benedict XVI

March 3, 2010

www.zenit.org

Dear brothers and

sisters,

Today I would like to speak about St. Bonaventure of Bagnoregio. I

confide to you that on proposing this theme I feel a certain nostalgia

because I remember the research that, as a young scholar, I carried out

precisely on this author, whom I particularly esteem. His knowledge has

been of no small influence in my formation. With great joy I went on

pilgrimage a few months ago to his birthplace, Bagnoregio, a small

Italian city, in Latium, which venerates his memory.

Born probably in 1217, he died in 1274; he lived in the 13th century, an

age in which the Christian faith, profoundly permeating the culture and

society of Europe, inspired immortal works in the field of literature,

visual arts, philosophy and theology. Striking among the great Christian

figures who contributed to the composition of this harmony between faith

and culture is, precisely, Bonaventure, man of action and of

contemplation, of profound piety and of prudence in governing.

He was called John of Fidanza. An incident that occurred when he was

still a boy profoundly marked his life, as he himself relates. He had

been affected by a serious illness and not even his father, who was a

doctor, hoped to save him from death. His mother appealed then to the

intercession of St. Francis of Assisi, canonized a short time earlier.

And John was cured. The figure of the Poverello of Assisi became even

more familiar a year later, when he was in Paris, where he had gone for

his studies. He had obtained the diploma of Master of Arts, which we

could compare to that of a prestigious secondary school of our time. At

that point, as so many young people of the past and also of today, John

asked himself a crucial question: "What must I do with my life?"

Fascinated by the witness of fervor and evangelical radicalism of the

Friars Minor, who had arrived in Paris in 1219, John knocked on the

doors of the Franciscan monastery of that city, and asked to be received

in the great family of the disciples of St. Francis.

Many years later, he explained the reasons for his choice: He recognized

the action of Christ in St. Francis and in the movement he initiated. He

wrote thus in a letter addressed to another friar: "I confess before God

that the reason that made me love more the life of Blessed Francis is

that it is similar to the origin and growth of the Church. The Church

began with simple fishermen, and was enriched immediately with very

illustrious and wise doctors; the religion of Blessed Francis was not

established by the prudence of men, but by Christ" (Epistula de tribus

quaestionibus ad magistrum innominatum, in Opere di San Bonaventura.

Intoduzione generale, Rome, 1990, p. 29).

Therefore, around the year 1243 John put on the Franciscan coarse woolen

cloth and took the name Bonaventure. He was immediately directed to

studies and frequented the faculty of theology of the University of

Paris, following a program of very difficult courses. He obtained the

different titles required by the academic career, those of "biblical

bachelor's" and "bachelor's in sentences." Thus Bonaventure studied in

depth sacred Scripture, the Sentences of Peter Lombard, the manual of

theology of that time, and the most important authors of theology and,

in contact with the teachers and students that arrived in Paris from the

whole of Europe, he matured his own personal reflection and a spiritual

sensitivity of great value that, in the course of the following years,

showed in his works and sermons, thus making him one of the most

important theologians of the history of the Church. It is significant to

recall the title of the thesis he defended to be able to qualify in the

teaching of theology, the licentia ubique docendi, as it was then

called. His dissertation was titled "Questions on Knowledge of Christ."

This argument shows the central role that Christ always had in the life

and teaching of Bonaventure. We can say, in fact, that all his thought

was profoundly Christocentric.

In those years in Paris, Bonaventure's adopted city, a violent dispute

broke out against the Friars Minor of St. Francis of Assisi and the

Friars Preachers of St. Dominic Guzmán. Debated was their right to teach

in the university and doubts were even cast on the authenticity of their

consecrated life. Certainly the changes introduced by the Mendicant

Orders in the way of understanding religious life, of which I spoke in

preceding catecheses, were so innovative that not everyone understood

them. Also added, as happens sometimes among sincerely religious

persons, were motives of human weakness, such as envy and jealousy.

Bonaventure, although surrounded by the opposition of the rest of the

university teachers, had already started to teach in the chair of

theology of the Franciscans and, to respond to those who were

criticizing the Mendicant Orders, he composed a writing titled

"Evangelical Perfection." In this writing he showed how the Mendicant

Orders, especially the Friars Minor, practicing the vows of poverty,

chastity and obedience, were following the counsels of the Gospel

itself. Beyond these historical circumstances, the teaching offered by

Bonaventure in this work of his and in his life is always timely: The

Church becomes luminous and beautiful by fidelity to the vocation of

those sons and daughters of hers who not only put into practice the

evangelical precepts, but who, by the grace of God, are called to

observe their advice and thus give witness, with their poor, chaste and

obedient lifestyle, that the Gospel is source of joy and perfection.

The conflict died down, at least for a certain period, and, by the

personal intervention of Pope Alexander IV, in 1257 Bonaventure was

officially recognized as doctor and teacher of the Parisian University.

Despite all this, he had to resign from this prestigious post, because

that same year the General Chapter of the order elected him

minister-general.

He carried out this task for 17 years with wisdom and dedication,

visiting the provinces, writing to brothers, intervening at times with a

certain severity to eliminate abuses. When Bonaventure began this

service, the Order of Friars Minor had developed in a prodigious way:

There were more than 30,000 friars spread over the whole of the West,

with a missionary presence in North Africa, the Middle East and also

Peking. It was necessary to consolidate this expansion and above all to

confer on it, in full fidelity to Francis' charism, unity of action and

spirit. In fact, among the followers of the Saint of Assisi there were

different forms of interpreting his message and the risk really existed

of an internal split. To avoid this danger, in 1260 the General Chapter

of the order in Narbonne accepted and ratified a text proposed by

Bonaventure, which unified the norms that regulated the daily life of

the Friars Minor. Bonaventure intuited, however, that the legislative

dispositions, though inspired in wisdom and moderation, were not

sufficient to ensure communion of spirit and hearts. It was necessary to

share the same ideals and the same motivations. For this reason,

Bonaventure wished to present the authentic charism of Francis, his life

and his teaching. Hence he gathered with great zeal documents related to

the Poverello and listened attentively to the memories of those who had

known Francis directly. From this was born a biography, historically

well founded, of the Saint of Assisi, titled Legenda Maior, written also

in a very succinct manner and called because of this the Legend. The

Latin word, as opposed to the Italian [and English, legend], does not

indicate a fruit of imagination but, on the contrary, Legenda means an

authoritative text, "to be read" officially. In fact, the General

Chapter of the Friars Minor of 1263, which met in Pisa, recognized in

St. Bonaventure's biography the most faithful portrait of the founder

and it thus became the official biography of the saint.

What is the image of St. Francis that arises from the heart and pen of

his devoted son and successor, St. Bonaventure? The essential point:

Francis is an alter Christus, a man who passionately sought Christ. In

the love that drives to imitation, he was entirely conformed to Him.

Bonaventure pointed out this living ideal to all of Francis' followers.

This ideal, valid for every Christian, yesterday, today and always, was

indicated as a program also for the Church of the Third Millennium by my

predecessor, the Venerable John Paul II. This program, he wrote in the

letter "Tertio Millennio Ineunte," is centered "on Christ himself, who

must be known, loved and imitated to live in Him the Trinitarian life,

and, with Him, to transform history to its fulfillment in the heavenly

Jerusalem" (No. 29).

In 1273 St. Bonaventure's life met with another change. Pope Gregory X

wished to consecrate him bishop and name him cardinal. He also asked him

to prepare a very important ecclesial event: the Second Ecumenical

Council of Lyon, whose objective was the re-establishment of communion

between the Latin and the Greek Churches. He dedicated himself to this

task with diligence, but was unable to see the conclusion of that

ecumenical summit, as he died while it was being held. An anonymous

papal notary composed a eulogy of Bonaventure, which offers us a

conclusive portrait of this great saint and excellent theologian: "Good,

affable, pious and merciful man, full of virtues, loved by God and by

men ... God, in fact, had given him such grace, that all those who saw

him were invaded by a love that the heart could not conceal" (cf. J.G.

Bougerol, Bonaventura, in A. Vauchez (vv.aa), Storia dei Santi e della

santita cristiana. Vol. VI. L'epoca del rinnovamento evangelico, Milan,

1991, p. 91).

Let us take up the legacy of this saint, doctor of the Church, who

reminds us of the meaning of our life with these words: "On earth ... we

can contemplate the divine immensity through reasoning and admiration;

in the heavenly homeland, instead, through vision, when we will be made

like to God, and through ecstasy --- we will enter into the joy of God"

(La conoscenza di Cristo, q. 6, conclusione, in Opere di San

Bonaventura. Opuscoli Teologici /1, Rome, 1993, p. 187).

[Translation by ZENIT]

[The Holy Father then greeted the people in several languages. In

English he said:]

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

In our catecheses on the Christian culture of the Middle Ages, we now

turn to Saint Bonaventure, an early follower of Saint Francis of Assisi

and a distinguished theologian and teacher in the University of Paris.

There Bonaventure was called upon to defend the new mendicant orders,

the Franciscans and the Dominicans, in the controversies which

questioned the authenticity of their religious charism. The Friars, he

argued, represent a true form of religious life, one which imitates

Christ by practising the evangelical counsels of poverty, chastity and

obedience. Elected Minister General of the Friars Minor, he served in

this capacity for seventeen years, at a time of immense expansion

accompanied by controversies about the genuine nature of the Franciscan

charism. His wisdom and moderation inspired the adoption of a rule of

life, and his biography of Francis, which presented the Founder as alter

Christus, a passionate follower of Christ, was to prove most influential

in consolidating the charism of the Franciscan Order. Named a Bishop and

Cardinal, Bonaventure died during the Council of Lyons. His writings

still inspire us by their wisdom penetrated by deep love of Christ and

mystical yearning for the vision of God and the joy of our heavenly

homeland.

I welcome the English-speaking pilgrims present at today’s Audience,

including those from Nigeria, Japan and the United States. To the

pilgrims from Sophia University in Tokyo I offer my prayerful good

wishes that the coming centenary of your University will strengthen your

service to the pursuit of truth and your witness to the harmony of faith

and reason. Upon you and your families I invoke God’s abundant

blessings!

©Copyright 2010 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

[He concluded in Italian:]

I greet, finally, youth, the sick and newlyweds. Dear young people,

prepare yourselves to address the important stages of life, basing every

plan of yours on fidelity to God and to your neighbor. Dear sick people,

offer your sufferings to the heavenly Father in union with those of

Christ, to contribute to the building of the Kingdom of God. And you,

dear newlyweds, know how to build daily your family in listening to God,

in faithful and mutual love.

[Translation by ZENIT]

Return to

General Audiences...

See Audience on St. Bonaventure's Concept of History...

See Audience on St. Bonaventure and St. Thomas' Approach to Theology...

Return to Lives of the Saints...

Look

at the One they Pierced!

This page is the work of

the Servants of the Pierced Hearts of Jesus and Mary