|

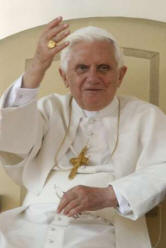

Pope Benedict XVI- General Audiences |

General

Audience

General

Audience

On the Mendicant Orders

"The Proposal of a 'Lay Sanctity' Won Many People"

H.H. Benedict XVI

January 13, 2010

www.zenit.org

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

At the beginning of the new year, we look at the history of

Christianity, to see how a history develops and how it can be renewed.

In it we can see that it is the saints, guided by the light of God, who

are the genuine reformers of the life of the Church and of society.

Teachers by their word and witnesses with their example, they know how

to promote a stable and profound ecclesial renewal, because they

themselves are profoundly renewed, they are in contact with the true

novelty: the presence of God in the world.

Such a consoling reality -- that in every generation saints are born and

bear the creativity of renewal -- constantly accompanies the history of

the Church in the midst of the sorrows and the negative aspects of her

journey. We also see come forth, century by century, the forces of

reform and of renewal, because the novelty of God is inexorable and

always gives new strength to go forward.

This was what happened in the 13th century, with the birth and the

extraordinary development of the Mendicant Orders: a model of great

renewal in a new historic period. They were called thus because of their

characteristic of "begging," namely, of going to the people humbly for

economic support to live the vow of poverty and to carry out their

evangelizing mission. Of the Mendicant Orders that arose in that period,

the most notable and most important are the Friars Minor and the

Preaching Friars, known as Franciscans and Dominicans. They have these

names because of their founders, Francis of Assisi and Dominic de Guzmßn,

respectively. These two great saints had the capacity to wisely read

"the signs of the times," intuiting the challenges that the Church of

their time had to face.

A first challenge was represented by the spread of several groups and

movements of faithful that, although inspired in a legitimate desire for

authentic Christian life, often placed themselves outside of ecclesial

communion. They were in profound opposition to the rich and beautiful

Church that developed precisely with the flourishing of monasticism. In

recent catecheses I reflected on the monastic community of Cluny, which

had always attracted young men and, therefore, vital forces, as well as

goods and riches. Thus logically developed, initially, a Church rich in

property and also immobile. Opposed to this Church was the idea that

Christ came on earth poor and that the true Church should be, in fact,

the Church of the poor; a desire for true Christian authenticity was

thus opposed to the reality of the empirical Church.

This brought about the so-called pauper movements of the Medieval Age.

They harshly contested the lifestyles of priests and monks of the time,

accused of having betrayed the Gospel and of not practicing poverty as

the first Christians, and these movements counterpoised to the ministry

of the bishops their own "parallel hierarchy." Moreover, to justify

their choices, they spread doctrines that were incompatible with the

Catholic faith. For example, the movement of the Cathars or Albigensians

proposed again old heresies, such as depreciation and contempt of the

material world -- opposition to wealth quickly became opposition to

material reality as such -- the negation of free will, and then dualism,

the existence of a second principle of evil equated with God. These

movements had success, especially in France and Italy, not only because

of their solid organization, but also because they denounced a real

disorder in the Church, caused by the less than exemplary behavior of

several representatives of the clergy.

On the other hand, the Franciscans and Dominicans, in the footsteps of

their founders, showed that it was possible to live evangelical poverty,

the truth of the Gospel, without separating from the Church; they showed

that the Church continued to be the true, authentic place of the Gospel

and Scripture. Thus, Dominic and Francis drew, precisely from profound

communion with the Church and the papacy, the strength of their witness.

With an altogether original choice in the history of consecrated life,

the members of these orders not only gave up possession of personal

goods, as monks had since antiquity, but even wanted real estate and

goods put in the name of the community. In this way they intended to

give witness of an extremely sober life, to be in solidarity with the

poor and trust only in Providence, to live every day by Providence, in

trust, putting themselves in God's hands. This personal and community

style of the Mendicant Orders, joined to total adherence to the teaching

of the Church and her authority, was greatly appreciated by the Pontiffs

of the time, such as Innocent III and Honorius III, who gave their full

support to these new ecclesial experiences, recognizing in them the

voice of the Spirit.

And fruits were not lacking: The poor groups that had separated from the

Church returned to ecclesial communion or, gradually, were

re-dimensioned until they disappeared. Also today, though living in a

society in which "having" often prevails over "being," there is great

sensitivity to examples of poverty and solidarity, which believers give

with courageous choices. Also today, similar initiatives are not

lacking: movements, which really begin from the novelty of the Gospel

and live it radically today, putting themselves in God's hands, to serve

their neighbor. The world, as Paul VI recalled in "Evangelii Nuntiandi,"

willingly listens to teachers when they are also witnesses. This is a

lesson that must never be forgotten in the endeavor of spreading the

Gospel: to live first of all what is proclaimed, to be a mirror of

divine charity.

Franciscans and Dominicans were witnesses, but also teachers. In fact,

another widespread need in their time was that of religious instruction.

Not a few lay faithful, who lived in greatly expanding cities, wished to

practice a spiritually intense Christian life. Hence they sought to

deepen their knowledge of the faith and to be guided in the arduous but

exciting path of holiness. Happily, the Mendicant Orders were also able

to meet this need: the proclamation of the Gospel in simplicity and in

its depth and greatness was one objective, perhaps the main objective of

this movement. In fact, with great zeal they dedicated themselves to

preaching. The faithful were very numerous, often real and veritable

crowds, which gathered to hear the preachers in the churches and in

places outdoors -- let us think of St. Anthony, for example. They dealt

with themes close to the life of the people, especially the practice of

the theological and moral virtues, with concrete examples, easily

understood. Moreover, they taught ways to nourish the life of prayer and

piety. For example, the Franciscans greatly spread devotion to the

humanity of Christ, with the commitment of imitating the Lord. Hence it

is not surprising that the faithful were numerous, women and men, who

chose to be supported in their Christian journey by the Franciscan and

Dominican friars, sought after and appreciated spiritual directors and

confessors.

Thus were born associations of lay faithful that were inspired by the

spirituality of Sts. Francis and Dominic, adapted to their state of

life. It was the Third Order, whether Franciscan or Dominican. In other

words, the proposal of a "lay sanctity" won many people. As the Second

Vatican Council recalled, the call to holiness is not reserved to some,

but is universal (cf. "Lumen Gentium," 40). In every state of life,

according to the needs of each, there is the possibility of living the

Gospel. Also today every Christian must tend to the "lofty measure of

Christian life," no matter what state of life he belongs to!

The importance of the Mendicant Orders grew so much in the Middle Ages

that lay institutions, such as labor organizations, ancient corporations

and even civil authorities, often took recourse to the spiritual

consultation of members of such orders for the writing of their

regulations and, at times, for the solution of internal and external

opposition. The Franciscans and Dominicans became the spiritual leaders

of the Medieval city. With great intuition, they put into practice a

pastoral strategy adapted to the transformation of society. Because many

people were moving from the countryside to the cities, they placed their

monasteries no longer in rural but in urban areas. Moreover, to carry

out their activity for the benefit of souls, it was necessary to move in

keeping with pastoral needs.

With another altogether innovative choice, the Mendicant Orders

abandoned the principle of stability, a classic of ancient monasticism,

to choose another way. Friars and Preachers traveled from one place to

another, with missionary zeal. As a consequence, they gave themselves an

organization that was different from that of the majority of monastic

orders. In place of the traditional autonomy that every monastery

enjoyed, they gave greater importance to the order as such and to the

superior-general, as well as to the structure of the provinces. Thus the

mendicants were in general available for the needs of the universal

Church. This flexibility made it possible to send friars more adapted to

specific missions and the Mendicant Orders reached North Africa, the

Middle East and Northern Europe. With this flexibility, missionary

dynamism was renewed.

Another great challenge was represented by the cultural transformations

taking place at that time. New questions made for lively discussions in

the universities, which arose at the end of the 12th century. Friars and

Preachers did not hesitate to assume this commitment as well and, as

students and professors, they entered the most famous universities of

the time, founded centers of study, produced texts of great value, gave

life to true and proper schools of thought, were protagonists of

scholastic theology in its greatest period, and significantly influenced

the development of thought.

The greatest thinkers, Sts. Thomas Aquinas and Bonaventure, were

mendicants, operating in fact with this dynamism of the new

evangelization, which also renewed the courage of thought, of dialogue

between reason and faith. Today also there is a "charity of and in

truth," an "intellectual charity" to exercise, to enlighten

intelligences and combine faith with culture. The widespread commitment

of the Franciscans and Dominicans in the Medieval universities is an

invitation, dear faithful, to make oneself present in places of the

elaboration of learning, to propose, with respect and conviction, the

light of the Gospel on the fundamental questions that concern man, his

dignity, and his eternal destiny. Thinking of the role of the

Franciscans and Dominicans in the Middle Ages, of the spiritual renewal

they aroused, of the breath of new life that they communicated in the

world, a monk says: "At that time the world was growing old. Two orders

arose in the Church, from which it renewed its youth, like that of an

eagle" (Burchard d'Ursperg, Chronicon).

Dear brothers and sisters, let us indeed invoke at the beginning of this

year the Holy Spirit, eternal youth of the Church: May he make each one

of us feel the urgency of giving a consistent and courageous witness of

the Gospel, so that saints will never be lacking, who make the Church

shine as a Bride always pure and beautiful, without stain and without

wrinkle, able to attract the world irresistibly to Christ, to his

salvation.

[Translation by ZENIT]

[At the end of the audience, the Holy Father greeted the people in

several languages. In English, he said:]

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

In our catechesis on medieval Christian culture, we now consider the

movement of ecclesial reform promoted by the two great Mendicant Orders.

In every age the saints are the true reformers of the Church's life. In

the thirteenth century Saints Francis and Dominic inspired a vast

evangelical renewal which met three significant needs of the Church of

that time. The Franciscans and the Dominicans adopted a lifestyle of

evangelical poverty which, unlike that of the Cathars, was grounded in

communion with the visible Church and a sound Christian understanding of

the goodness of creation. As zealous preachers, especially in urban

environments, the Friars provided religious instruction and spiritual

guidance to the lay faithful, many of whom became members of their

"Third Orders." Traveling freely from place to place, they also

contributed to the overall renewal of Church life and the spiritual

transformation of society. By their presence in the universities, the

Friars worked for the evangelization of culture, affirming the harmony

of faith and reason, and creating the great synthesis of scholastic

theology. May their example of holiness and evangelical lifestyle

inspire our own witness to the Gospel and our efforts to draw the world

to Christ and his Church.

I offer a warm welcome to the English-speaking visitors present at

today's Audience, especially those from Denmark, Australia and the

United States of America. My particular greeting goes to the many

student groups present and to the faculty members. Upon all of you I

invoke God's blessings of joy and peace!

Copyright 2010 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

[In Italian, he added]

Finally, as usual, I turn to the young people, the sick and the

newlyweds present. Today's liturgy remembers St. Hilary, bishop of

Poitiers, who lived in France in the 4th century, who "was a tenacious

champion of the divinity of Christ" (Liturgy), defender of the faith and

teacher of truth. May his example sustain you, dear young people, in

your constant and courageous search for Christ: Especially you students

of the Diocese of Caserta, thank you for your presence and thank you for

your commitment in the faith. I see and feel the strength of your faith;

I encourage you, dear sick people, to offer your sufferings so that the

Kingdom of God is spread in the whole world; and help you, dear

newlyweds, to be witnesses of the love of Christ in family life.

I now wish to address an appeal for the tragic situation currently being

experienced in Haiti. My thoughts go in particular to the population hit

just a few hours ago by a devastating earthquake which has caused

serious loss of human life, large numbers of homeless and missing

people, and vast material damage. I invite everyone to join my prayers

to the Lord for the victims of this catastrophe and for those who mourn

their loss. I give assurances of my spiritual closeness to people who

have lost their homes and to everyone who, in various ways, has been

affected by this terrible calamity, imploring God to bring them

consolation and relief in their suffering.

I appeal to the generosity of all people so that these our brothers and

sisters who are experiencing a moment of need and suffering may not lack

our concrete solidarity and the effective support of the international

community. The Catholic Church will not fail to move immediately,

through her charitable institutions, to meet the most immediate needs of

the population.

[Translation by ZENIT]

ęCopyright 2009 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Look

at the One they Pierced!

This page is the work of

the Servants of the Pierced Hearts of Jesus and Mary