|

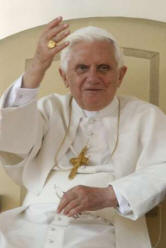

Pope Benedict XVI- General Audiences |

General

Audience

General

Audience

On Rupert of Deutz

"We Can Also, Each One in His Own Way, Find the Lord Jesus"

H.H. Benedict XVI

December 9, 2009

www.zenit.org

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

Today we come to know another Benedictine monk of the 12th century. His

name is Rupert of Deutz, a city near Cologne, headquarters of a famous

monastery. Rupert himself speaks of his life in one of his most

important works, "The Glory and Honor of the Son of Man," which is a

partial commentary on the Gospel of Mark. While still a child, he was

received as an "oblate" in the Benedictine monastery of St. Lawrence of

Liege, according to the custom of the age to entrust one of the children

to the education of monks, intending to make of him a gift to God.

Rupert always loved the monastic life. He very soon learned the Latin

language to study the Bible and to enjoy the liturgical celebrations. He

was distinguished for his absolutely upright moral rectitude and for his

strong attachment to the See of St. Peter.

His times were marked by opposition between the papacy and the empire,

due to the so-called investiture conflict, with which -- as I have

pointed out in other catecheses -- the papacy wished to prevent the

appointment of bishops and the exercise of their jurisdiction from

depending on the civil authority, which was guided in the main by

political and economic motivations, and certainly not pastoral ones.

Otbert, the bishop of Liege, resisted the Pope's directives and sent

Berengarius, abbot of the monastery of St. Lawrence, into exile,

precisely for his fidelity to the Pontiff. Rupert lived in that

monastery, and he did not hesitate to follow his abbot into exile. Only

when Bishop Otbert re-entered into communion with the Pope did Rupert

return to Liege and accept priestly ordination. Up to that moment, in

fact, he had avoided receiving ordination from a bishop in disagreement

with the Pope. Rupert teaches us that when controversies arise in the

Church, reference to the Petrine ministry guarantees fidelity to sound

doctrine and gives interior serenity and liberty. After the dispute with

Otbert, he still had to leave his monastery two more times. In 1116 the

adversaries in fact wanted to prosecute him. Although acquitted from

every accusation, Rupert preferred to go for a time to Siegbur, but

because the controversies had not yet ceased when he returned to the

monastery in Liege, he decided to establish himself definitively in

Germany. Appointed abbot of Deutz in 1120, he remained there until 1129,

the year of his death. He left only for a pilgrimage to Rome in 1124.

A prodigious writer, Rupert left very numerous works, still of great

interest today, in part because he was active in several important

theological discussions of the time. For example, he intervened with

determination in the Eucharistic controversy that in 1077 led to the

condemnation of Berengarius of Tours. The latter had given a reductive

interpretation of the presence of Christ in the sacrament of the

Eucharist, describing it as only symbolic. The term "transubstantiation"

had still not entered the language of the Church, but Rupert, using at

times audacious expressions, made himself a determined supporter of the

reality of the Eucharist. Above all in a work titled "De divinis

officiis" (The Divine Offices), he affirmed with determination the

continuity between the Body of the Word Incarnate of Christ and that

present in the Eucharistic species of bread and wine. Dear brothers and

sisters, it seems to me that at this point we must also think of our

time; the danger exists also today of re-appraising the Eucharistic

realism, to consider, that is, the Eucharist almost as just a rite of

communion, of socialization, forgetting too easily that the risen Christ

is really present -- with his risen body -- which is placed in our hands

to draw us out of ourselves, to be incorporated in his immortal body and

thus lead us to new life. This great mystery that the Lord is present in

all his reality in the Eucharistic species is a mystery to be adored and

loved always anew!

I would like to quote here the words of the Catechism of the Catholic

Church which bear in themselves the fruit of the meditation of the faith

and of the theological reflection of 2,000 years: "The mode of Christ's

presence under the Eucharistic species is unique. It raises the

Eucharist above all the sacraments as 'the perfection of the spiritual

life and the end to which all the sacraments tend.' In the most blessed

sacrament of the Eucharist 'the body and blood, together with the soul

and divinity, of our Lord Jesus Christ and, therefore, the whole Christ

is truly, really, and substantially contained'" (CCC, 1374). With his

reflection, Rupert was a contributor to this precise formulation.

Another controversy in which the abbot of Deutz was involved refers to

the problem of the reconciliation of the goodness and omnipotence of God

and the existence of evil. If God is omnipotent and good, how does one

explain the reality of evil? Rupert in fact reacted to the positions

assumed by the teachers of the theological school of Laon, who with a

series of philosophical reasonings distinguished in God's will

"approval" and "permission," concluding that God permits evil without

approving it and, hence, without willing it. Rupert, instead, gave up

the use of philosophy, which he considered inadequate in the face of

such a great problem, and remained simply faithful to the biblical

account. He begins from the goodness of God, from the truth that God is

most good and cannot but desire goodness. Thus he singles out the origin

of evil in man himself and in the mistaken use of human liberty. When

Rupert addresses this argument, he writes pages full of religious

inspiration to praise the Father's infinite mercy and the patience and

benevolence of God toward sinful man.

As other theologians of the Middle Ages, Rupert also asked himself: Why

did the Word of God, the Son of God, become man? Some, many, responded

explaining the incarnation of the Word with the urgency of repairing

man's sin. Rupert, instead, with a Christocentric vision of the history

of salvation, widens this perspective, and in one of his works titled

"The Glorification of the Trinity," holds the position that the

Incarnation, the central event of history, was foreseen from all

eternity, even independently of man's sin, so that all creation could

give praise to God the Father and love him as in one family gathered

around Christ, the Son of God. He sees then in the pregnant woman of

Revelation the whole history of humanity, which is oriented to Christ,

just as conception is oriented to birth, a perspective that will be

developed by other thinkers and put to good use also by contemporary

theology, which affirms that the whole history of the world and of

humanity is conception oriented to the birth of Christ.

Christ is always at the center of exegetical explanations furnished by

Rupert in his comments on the books of the Bible, to which he dedicated

himself with great diligence and passion. He thus rediscovers a

wonderful unity in all the events of the history of salvation, from the

creation to the final consummation of time: "The whole of Scripture," he

affirms, "is just one book, which tends to the same end [the divine

Word]; which comes from one God and which was written by only one

Spirit" (De glorificatione Trinitatis et processione Sancti Spiritus I,

V, PL 169, 18).

In the interpretation of the Bible, Rupert does not limit himself to

repeat the teaching of the Fathers, but shows his originality. For

example, he is the first writer who identified the bride of the Canticle

of Canticles with Mary Most Holy. Thus his commentary on this book of

Scripture is a sort of Mariological summa, in which are presented the

privileges and the excellent virtues of Mary. In one of the most

inspired passages of his commentary, Rupert writes: "O most beloved

among the beloved, Virgin of virgins, what in you is praised by your

beloved Son, whom the entire choir of angels exalts? Praised are

simplicity, purity, innocence, doctrine, modesty, humility, the

integrity of mind and flesh, in other words, the untainted virginity"

(In Canticum Canticorum 4, 1-6, CCL 26, pp. 69-70). Rupert's Marian

interpretation of the Canticle is a good example of the harmony between

liturgy and theology. In fact, several passages of this biblical Book

were already used in the liturgical celebrations of Marian feasts.

Moreover, Rupert took care to insert his Mariological doctrine in

ecclesiological doctrine. In other words, he saw in Mary Most Holy the

most holy part of the whole Church. See why my venerated predecessor,

Pope Paul VI, in the closing address of the third session of the Second

Vatican Council, solemnly proclaiming Mary Mother of the Church, quoted

in fact a proposal treated in Rupert's works, who describes Mary as

portio maxima, portio optima -- the loftiest part, the best part of the

Church (cf. In Apocalypsem 1.7, PL 169, 1043).

Dear friends, from this hasty sketch we recall that Rupert was a fervent

theologian, gifted with great depth. As all the representatives of

monastic theology, he was able to combine the rational study of the

mysteries of the faith with prayer and contemplation, considered the

summit of all knowledge of God. He himself speaks sometimes of his

mystical experiences, as when he confides about the ineffable joy of

having perceived the presence of the Lord: "In that brief moment," he

affirms, "I experienced how true that is which he himself says: Learn

from me, for I am meek and humble of heart" (De gloria et honore Filii

hominis. Super Matthaeum 12, PL 168, 1601). We can also, each one in his

own way, find the Lord Jesus who endlessly accompanies us on our way,

makes himself present in the Eucharistic bread and in his Word for our

salvation.

[Translation by ZENIT]

[The Holy Father then addressed the people in various languages. In

English, he said:]

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

In our catechesis on the Christian culture of the Middle Ages, we now

turn to Rupert of Deutz, an outstanding theologian of the twelfth

century. Rupert experienced at first hand the conflict between the

Empire and the Church linked to the investiture crisis, and he played a

significant role in the principal theological debates of his day. He

forcefully defended the reality of Christ's real presence in the

Eucharist, and insisted that the origin of evil is to be found in man's

mistaken use of freedom, not in the positive will of God. Rupert also

contributed to the medieval discussion of the purpose of the

Incarnation, which he set within the vast vision of history centred on

Christ. His teaching on the dignity and privileges of the Virgin Mary,

presented with a broad ecclesiological context, would prove influential

for later theology and find an echo in the doctrine of the Second

Vatican Council. Rupert's ability to harmonize the rational study of the

mysteries of faith with prayer and contemplation makes him a typical

representative of the monastic theology of his time. His example

inspires us to draw near to Christ, present among us in his Word and in

the Eucharist, and to rejoice in the knowledge that he remains with us

at every moment of our lives and throughout history.

I offer a warm welcome to the English-speaking pilgrims and visitors

present at today's Audience. I greet especially the groups from South

Korea, South Africa and the United States of America. As we prepare with

joy to celebrate our Saviour's birth this Christmas, let us renew our

commitment to bring the light of Christ to those we meet. May God bless

you all!

© Copyright 2009 -- Libreria Editrice Vaticana

[In Italian, he said:]

Finally, I greet young people, the sick and newlyweds. The solemnity of

the Immaculate Conception, which we celebrated yesterday, reminds us of

Mary's singular adherence to God's salvific plan. Dear young people,

make an effort to imitate her with a pure and transparent heart, letting

yourselves be molded by God who also in you wills to "do great things"

(cf. Luke 1:49). Dear sick people, with the help of Mary always trust

the Lord, who knows your sufferings and, uniting them to his, offers

them for the salvation of the world. And you, dear newlyweds, make your

home in imitation of that of Nazareth, welcoming and open to life.

[Translation by ZENIT]

© Innovative Media, Inc.

Look

at the One they Pierced!

This page is the work of

the Servants of the Pierced Hearts of Jesus and Mary