|

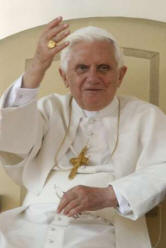

Pope Benedict XVI- General Audiences |

General

Audience

General

Audience

On John of Salisbury

"We Witness a Worrying Separation Between Reason ... and Liberty"

H.H. Benedict XVI

December 16, 2009

www.zenit.org

Dear brothers and sisters,

Today we will meet the figure of John of Salisbury, who belonged to one

of the most important philosophical and theological schools of the

Middle Ages, that of the cathedral of Chartres, in France. John, too,

like the theologians about whom I've spoken over the past weeks, helps

us to understand how faith, in harmony with the just aspirations of

reason, pushes thought toward revealed truth, in which the true good of

man is found.

John was born in England, in Salisbury, between the year 1100 and 1120.

Reading his works, and above all, his rich epistles, we discover the

most important events of his life. For 12 years, between 1136 and 1148,

he dedicated himself to study, availing of the most qualified schools of

the epoch, where he heard lectures from famous teachers.

He headed to Paris and then to Chartres, the environment that

particularly marked his formation and from which he assimilated his

great cultural openness, his interest for speculative problems, and his

appreciation of literature. As often happened in that time, the most

brilliant students were picked by prelates and sovereigns, to be their

closest collaborators. This also happened to John of Salisbury, who was

presented by a great friend of his, Bernard of Claraval, to Archbishop

Theobald of Canterbury -- the primary see of England -- who happily took

him in among his clergy.

For 11 years, from 1150 to 1161, John was the secretary and chaplain of

the elderly archbishop. With tireless zeal, despite continuing his

studies, he carried out an intense regimen of diplomatic activities,

traveling 10 times to Italy with the specific objective of nourishing

the relationship of the kingdom of England and the Church there with the

Roman Pontiff.

Among other things, during those years, the Pope was Adrian IV, an

Englishman who was a close friend of John of Salisbury. In the years

following the 1159 death of Adrian IV, a situation of serious tension

was created in England between the Church and the kingdom. The king,

Henry II, aimed to wield authority over the internal life of the Church,

limiting its liberty. This endeavor brought about a reaction from John

of Salisbury, and above all, valiant resistance from Theobald's

successor in the episcopal see of Canterbury, St. Thomas Becket. St.

Thomas went to exile in France because of this. John of Salisbury

accompanied him and remained at his service, always working for

reconciliation. In 1170, when both John and Thomas Becket had returned

to England, Thomas was attacked and killed in the cathedral. He died as

a martyr and was immediately venerated as such by the people.

John continued faithfully serving the successor of Thomas as well, until

he was elected bishop of Chartres, where he stayed from 1176 to 1180,

the year of his death.

I would like to point out two of John of Salisbury's works, which are

considered his masterpieces and which are elegantly named with the Greek

titles of "Metalogicon" (In Defense of Logic) and "Policraticus" (The

Man of Government).

In the first work -- and not lacking that fine irony that characterizes

many men of culture -- he rejects the position of those who had a

reductionist concept of culture, considering it empty eloquence and

useless words. John instead praises culture, authentic philosophy, that

is, the encounter between clear thought and communication, efficient

speech. He writes, "As in fact eloquence that is not enlightened by

faith is not only rash but also blind, so wisdom that does not engage in

the use of the word not only is weak, but in a certain way, is

truncated: Although perhaps wisdom without words could be of benefit to

the individual conscience, rarely and little does it benefit society" (Metalogicon

1,1 PL 199,327).

This is a very relevant teaching. Today, what John defines as

"eloquence," that is, the possibility of communicating with instruments

ever more elaborate and widespread, has enormously increased. For all

that, there is an even more urgent need to communicate messages gifted

with "wisdom," that is, messages inspired in truth, goodness and beauty.

This is a great responsibility that particularly involves those who work

in the multiform and complex realm of culture, communication and the

media. And this is a realm in which the Gospel can be announced with

missionary vigor.

In "Metalogicon," John takes up the problems of logic, which were

something of great interest in his time, and he proposes a fundamental

question: What can human reason come to know? Up to what point can it

respond to this aspiration that is in every person, that of seeking the

truth? John of Salisbury takes a moderate position, based in the

teaching of certain treatises of Aristotle and Cicero. According to him,

ordinarily human reason can reach knowledge that is not indisputable,

but probable and contestable. Human knowledge -- this is his conclusion

-- is imperfect, because it is subject to finitude, to the limits of

man. Nevertheless, it increases and becomes perfected thanks to

experience and the elaboration of correct and concrete reasoning,

capable of establishing relationships between concepts and reality;

thanks to discussion, to confrontation, and to knowledge that is

enriched from one generation to another. Only in God is there a perfect

knowledge, which is communicated to man, at least partially, by means of

revelation welcomed in faith. Thus the knowledge of faith opens the

potentialities of reason and brings it to advance with humility in

knowledge of the mysteries of God.

The believer and the theologian, who go deeper into the treasure of the

faith, are opened as well to a practical knowledge that guides daily

activity, that is, moral law and the exercise of virtue.

John of Salisbury writes: "The clemency of God has conceded us his law,

which establishes what is useful for us to know, and indicates how much

is licit to know of God and how much is justifiable to investigate. ...

In this law, in fact, the will of God is made explicit and manifested,

so that each one of us knows what is necessary for him to do" (Metalogicon

4,41, PL 199,944-945).

According to John of Salisbury, there also exists an objective and

immutable truth, whose origin is God, accessible to human reason. This

truth regards practical and social actions. This is a natural law, from

which human laws and political and religious authority should take

inspiration, so that they can promote the common good. This natural law

is characterized by a property that John calls "equity," that is, the

attribution to each person of his rights. From here descend precepts

that are legitimate for all peoples and which in no case can be

abrogated. This is the central thesis in "Policraticus," the treatise on

philosophy and political theology, in which John of Salisbury reflects

on the conditions that enable a political leader to act in a just and

authorized manner.

While other discussions taken up in this work are tied to the historical

circumstances in which it was written, the theme of the relationship

between natural law and a positive-juridical ordering, arbitrated by

equity, is still today of great importance. In our times, in fact, above

all in certain countries, we witness a worrying separation between

reason, which has the task of discovering the ethical values linked to

the dignity of the human person, and liberty, which has the

responsibility of welcoming and promoting these values. Perhaps John of

Salisbury would remind us today that only those laws are equitable that

protect the sanctity of human life and reject the legalization of

abortion, euthanasia and limitless genetic experimentation, those laws

that respect the dignity of matrimony between a man and a woman, that

are inspired in a correct secularity of state -- secularity that always

includes the protection of religious liberty -- and that pursue

subsidiarity and solidarity at the national and international level.

If not, what John of Salisbury calls the "tyranny of the sovereign" or,

what we would call "the dictatorship of relativism," ends up taking over

-- a relativism that, as I recalled some years ago, "recognizes nothing

as definitive and that has as its measure only the self and its desires"

(Misa pro eligendo Romano Pontifice, homily, April 19, 2005).

In my most recent encyclical, "Caritas in Veritate," addressing men and

women of good will, who endeavor to ensure that social and political

action is never disconnected from the objective truth about man and his

dignity, I wrote: "Truth, and the love which it reveals, cannot be

produced: they can only be received as a gift. Their ultimate source is

not, and cannot be, mankind, but only God, who is himself Truth and

Love. This principle is extremely important for society and for

development, since neither can be a purely human product; the vocation

to development on the part of individuals and peoples is not based

simply on human choice, but is an intrinsic part of a plan that is prior

to us and constitutes for all of us a duty to be freely accepted" (No.

52).

This plan that is prior to us, this truth of being, we should seek and

welcome, so that justice is born. But we can find it and welcome it only

with a heart, a will and reason purified in the light of God.

[Translation by ZENIT]

[At the end of the audience, the Holy Father greeted the people in

several languages. In English, he said:]

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

In our catechesis on the Christian culture of the Middle Ages, we now

turn to John of Salisbury, an outstanding philosopher and theologian of

the twelfth century. Born in England, John was educated in Paris and

Chartres. A close associate of Saint Thomas Becket, he was involved in

the crisis between the Church and the Crown under King Henry II, and

died as Bishop of Chartres. In his celebrated work, the Metalogicon,

John teaches that authentic philosophy is by nature communicative: it

bears fruit in a message of wisdom which serves the building up of

society in truth and goodness. While acknowledging the limitations of

human reason, John insists that it can attain to the truth through

dialogue and argumentation. Faith, which grants a share in Godís perfect

knowledge, helps reason to realize its full potential. In another work,

the Policraticus, John defends reasonís capacity to know the objective

truth underlying the universal natural law, and its obligation to embody

that law in all positive legislation. Johnís insights are most timely

today, in light of the threats to human life and dignity posed by

legislation inspired more by the "dictatorship of relativism" than by

the sober use of right reason and concern for the principles of truth

and justice inscribed in the natural law.

I offer a warm welcome to the student groups present today from England,

Ireland and the United States. My cordial greeting also goes to the

pilgrims from Kenya and Nigeria. Upon all the English-speaking pilgrims

and visitors present at todayís Audience, I invoke Godís blessings of

joy and peace!

© Copyright 2009 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

[He added in Italian:]

With great affection, I greet you dear youth, ill people and newlyweds.

In this period of Advent, the Lord tells us in the words of the Prophet

Isaiah, "Turn to me and be saved" (45:22). Dear boys and girls, coming

from so many schools and parishes of Italy, leave space in your heart

for Jesus who comes to give testimony of his joy and peace. Dear sick

people, welcome the Lord in your lives so as to find support and

consolation in the encounter with him. And dear newlyweds, make of the

message of the love of Christmas the rule of life for your families.

[Translation by ZENIT]

Look

at the One they Pierced!

This page is the work of

the Servants of the Pierced Hearts of Jesus and Mary