|

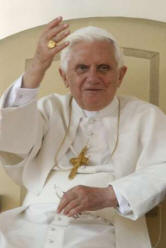

Pope Benedict XVI- General Audiences |

General

Audience

General

Audience

On Theology of the Heart or the Mind

"To Make Truth Triumph in Charity"

H.H. Benedict XVI

November 4, 2009

www.zenit.org

Dear brothers and sisters,

In the last catechesis I presented the main characteristics of 12th

century monastic and scholastic theology, which in a certain sense we

could call, respectively, "theology of the heart" and "theology of

reason." A wide debate, at times fiery, took place between the

representatives of each current, represented symbolically by the

controversy between St. Bernard of Clairvaux and Abelard.

To understand this confrontation between the two great teachers, it is

good to recall that theology is the search for a rational understanding,

insofar as possible, of the mystery of Christian revelation, believed by

faith: fides quaerens intellectum -- faith seeking understanding -- to

use a traditional, concise and effective definition.

Now, whereas St. Bernard, typical representative of monastic theology,

places the accent on the first part of the definition, that is, on fides

-- faith, Abelard, who is a scholastic, stresses the second part, that

is, the intellectus -- on understanding through reason. For Bernard,

faith itself is gifted with a profound certainty based on the testimony

of Scripture and on the teaching of the Church fathers. Faith, moreover,

is reinforced by the testimony of the saints and by the inspiration of

the Holy Spirit in the soul of each believer. In cases of doubt or

ambiguity, faith must be protected and enlightened by the exercise of

the ecclesial magisterium.

So for Bernard it is difficult to agree with Abelard and, more

generally, with those who subjected the truths of the faith to the

critical examination of reason, an examination that, in his opinion,

entailed a grave danger, intellectualism, the relativization of truth,

discussion of the very truths of the faith. Bernard saw in this way of

proceeding an audacity to the point of lacking scruples, fruit of the

pride of human intelligence, which attempts to "grasp" the mystery of

God. Pained, he wrote thus in one of his letters: "Human wit grasps

everything, leaving nothing to faith. It confronts what is beyond it;

scrutinizes what is superior to it; invades the world of God; alters,

more than illumines, the mysteries of the faith; it does not open what

is closed and sealed, but eradicates it, and what is does not find

viable, it considers as nothing, and refuses to believe in it" (Epistola

CLXXXVIII,1: PL 182, I, 353).

For Bernard, theology has only one end: that of promoting the intense

and profound experience of God. Therefore, theology is an aid to love

the Lord ever more and better, as states the title of the treatise on

the Duty to Love God (De diligendo Deo). Along this way, there are

different degrees, which Bernard describes in detail, up to the highest,

when the soul of the believer is inebriated on the summits of love. The

human soul can attain already on earth that mystical union with the

Divine Word, a union that the doctor mellifluus describes as "spiritual

espousals." The Divine Word visits her, eliminates the last resistances,

illumines her, inflames her and transforms her. In this mystical union,

[the soul] enjoys great peace and sweetness, and sings to her Spouse a

hymn of joy. As I reminded in the catechesis dedicated to the life and

doctrine of St. Bernard, for him theology cannot but be nourished by

contemplative prayer, in other words, by the affective union of the

heart and mind with God.

Abelard, on the other hand, who is precisely the one who introduced the

term "theology" in the sense in which we understand it today, places

himself in a different perspective. Born in Brittany, in France, this

famous teacher of the 12th century was gifted with a very acute

intelligence and his vocation was study. He concerned himself first with

philosophy, and then applied the results obtained in this discipline to

theology, which he taught in Paris, the most cultured city of the time,

and subsequently, in the monasteries in which he lived. He was a

brilliant orator: His lessons were followed by true and proper masses of

students.

Of a religious spirit but of a restless personality, his life was full

of dramatics: He refuted his teachers, had a child with Eloise, an

educated and intelligent woman. He was often in controversy with his

theological colleagues. He also suffered ecclesiastical condemnations,

though he died in full communion with the Church, to whose authority he

submitted with a spirit of faith.

In fact St. Bernard contributed to the condemnation of some of Abelard's

doctrines in the provincial synod of Sens of 1140, and he also requested

the intervention of Pope Innocent II. The abbot of Clairvaux rejected,

as we recalled, Abelard's too-intellectualist method, which in his eyes

reduced the faith to a simple opinion detached from revealed truth.

Bernard's fears were not unfounded, but were shared, moreover, by other

great thinkers of his time. In fact, an excessive use of philosophy made

Abelard's Trinitarian doctrine dangerously fragile, and thus his idea of

God. In the moral field his teaching was not lacking in ambiguity: He

insisted on considering the individual's intention as the only source to

describe the goodness or evil of moral acts, thus neglecting the

objective meaning and moral values of actions: a dangerous subjectivism.

This is -- as we know -- a very pertinent element for our times, in

which culture often seems marked by a growing tendency to ethical

relativism: only the "I" decides what is good for me, at this moment.

However, we must not forget the great merits of Abelard, who had many

disciples and who contributed to the development of scholastic theology,

destined to express itself in a more mature and fruitful way in the next

century. Some of his intuitions should not be undervalued, as for

example when he affirms that in non-Christian religious traditions there

is already a preparation for the acceptance of Christ, Divine Word.

What can we learn today from the often heated confrontation between

Bernard and Abelard and, in general, between monastic and scholastic

theology? Above all I believe it shows the usefulness of and the need

for a healthy discussion in the Church, especially when the questions

debated have not been defined by the magisterium, which continues to be,

however, an essential point of reference. St. Bernard, but also Abelard

himself, always recognized, without doubting, its authority. Moreover,

the condemnations that the latter suffered remind us that in the

theological field there must be a balance between what we might call the

architectonic principles that have been given to us by Revelation and

that, because of this, always are of prime importance, and the

interpretative principles suggested by philosophy, that is, by reason,

which has an important function, but only instrumental. When this

balance between the architecture and the instruments of interpretation

diminishes, theological reflection runs the risk of being contaminated

with errors, and then it corresponds to the magisterium to exercise that

necessary service to truth that is proper to it.

Moreover, it must be emphasized that, between the motivations that

induced Bernard to place himself against Abelard and to request the

intervention of the magisterium, was, also, the concern to safeguard

simple and humble believers, who must be defended when they run the risk

of being confused or led astray by opinions that are too personal and by

theological argumentations without scruples, which might endanger their

faith.

Finally, I would like to recall that the theological confrontation

between Bernard and Abelard ended with full reconciliation between them,

thanks to the mediation of a common friend, Peter the Venerable, abbot

of Cluny, of whom I spoke in a previous catechesis. Abelard showed

humility in acknowledging his errors; Bernard used great benevolence.

There prevailed in both what should truly be in the heart when a

theological controversy is born, that is, to safeguard the faith of the

Church and to make truth triumph in charity. May this also be the

attitude with which there are confrontations in the Church, always

keeping as the aim the pursuit of truth.

[Translation by ZENIT]

[The Pope then greeted the people in several languages. In English, he

said:]

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

Today we continue our comparison of the monastic and scholastic

approaches to theology which we began last week, by looking again at

Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, this time in comparison with Abelard. Both

of them considered theology as "faith seeking understanding"; but

whereas Bernard placed the accent on "faith," Abelard emphasized

"understanding." Bernard, for whom the aim of theology was to have a

living experience of God, cautioned against intellectual pride which

makes us think we can grasp fully the mysteries of faith. Abelard, who

strove to apply the insights of philosophy to theology, saw in other

religions the seeds of an openness to Christ. The respective approaches

of Bernard and Abelard -- one a "theology of the heart" and the other a

"theology of reason" -- were not without tension. They therefore

illustrate the importance of healthy theological discussion and humble

obedience to ecclesial authority. Theology must respect the principles

it receives from revelation as it uses philosophy to interpret them.

Whenever a theological dispute arises, everyone, and in a particular way

the Magisterium, has a responsibility to safeguard the integrity of the

faith. As we strive to deepen our understanding of the Gospel, may God

strengthen us to extol its truth in charity.

I am pleased to welcome the English-speaking pilgrims present at today's

Audience. I particularly greet priests from the dioceses of England and

Wales celebrating Jubilees, pilgrims from the Diocese of Wichita,

students and teachers from Catholic schools in Denmark, and Catholic

nurses from the United States. God's blessings upon you all!

ęCopyright 2009 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

[He added in Italian:]

I greet, finally, young people, the sick and newlyweds. Today is the

liturgical memorial of St. Charles Borromeo, famous bishop of the

Diocese of Milan, who, animated by ardent love for Christ, was a

tireless teacher and guide. May his example help you, dear young people,

to let yourselves be led by Christ in your daily choices; may it

encourage you, dear sick people, to offer your suffering for the pastors

of the Church and for the salvation of souls; may it support you, dear

newlyweds, in founding your family on evangelical values.

[Translation by ZENIT]

Look

at the One they Pierced!

This page is the work of

the Servants of the Pierced Hearts of Jesus and Mary