|

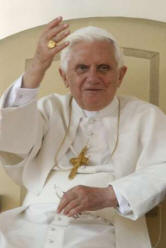

Pope Benedict XVI- General Audiences |

General

Audience

General

Audience

On What Europe Owes to Cluny

"The Value of the Human Person and the Primary Good of Peace"

H.H. Benedict XVI

November 11, 2009

www.zenit.org

Dear brothers and sisters,

This morning I wish to speak of a monastic movement that had great

importance in the Medieval centuries, and to which I have already

referred in previous catecheses. It is about the Order of Cluny, which,

at the beginning of the 12th century, the time of its greatest

expansion, had almost 1,200 monasteries: a really impressive figure!

In fact at Cluny, 1,100 years ago, in 910, a monastery was founded and

placed under the guidance of Abbot Bernone, after the donation of

William the Pious, Duke of Aquitaine. At that time Western monasticism,

which flowered some centuries before with St. Benedict, was very

impoverished for several reasons: the unstable political and social

conditions due to the constant invasions and devastation of people not

integrated in the European fabric, widespread poverty and above all the

dependence of abbeys on local lords, who controlled everything that

belonged to the territory of their competence. In such a context, Cluny

represented the soul of a profound renewal of monastic life, to lead it

back to its original inspiration.

Represented at Cluny was the observance of the Rule of St. Benedict with

some adaptations already introduced by other reformers. Above all the

intention was to guarantee the central role that the liturgy must have

in Christian life. The monks of Cluny dedicated themselves with love and

great care to the celebration of the Liturgy of the Hours, the singing

of psalms, to processions both devotional and solemn and, above all, to

the celebration of Holy Mass. They promoted sacred music; they wanted

architecture and art to contribute to the beauty and solemnity of the

rites; they enriched the liturgical calendar with special celebrations

such as, for example, the commemoration of the faithful deceased at the

beginning of November, which we also celebrated a short time ago; the

they enhanced devotion to the Virgin Mary.

So much importance was given to the liturgy because the monks of Cluny

were convinced that it was participation in the liturgy of Heaven. And

the monks felt responsible to intercede at the altar of God for the

living and the dead, given that very many faithful repeatedly requested

them to be remembered in prayer. On the other hand, it was precisely for

this purpose that William the Pious had desired the birth of the Abbey

of Cluny. In the ancient document, which attests to the foundation, we

read: "With this gift I establish that a monastery of regulars be built

at Cluny in honor of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul, and that monks

gather here who live according to the Rule of St. Benedict (...) and

that it be a venerable asylum of prayer which is frequented with vows

and supplications, seeking and yearning with every desire and profound

ardor the celestial life, and assiduous prayers, invocations and

supplications addressed to the Lord."

To guard and nourish this climate of prayer, the rule of Cluny

emphasized the importance of silence, a discipline to which the monks

willingly submitted themselves, convinced that the purity of the

virtues, to which they aspired, required profound and constant

recollection. It is no wonder that very soon, fame for holiness was

attributed to the monastery of Cluny, and that many other monastic

communities decided to follow its practices. Many princes and popes

requested the abbots of Cluny to spread their reform, to the point that

in a short time a multitudinous network of monasteries were linked to

Cluny, wither with true and proper juridical links or a sort of

charismatic affiliation. Thus a Europe of the spirit was being

delineated in the different regions of France, Italy, Spain, Germany and

Hungary.

The success of Cluny was assured first of all by the lofty spirituality

cultivated there, but also by some other conditions that favored its

development. As opposed to what had happened up to then, the monastery

of Cluny and the communities depending on it were exempted from the

jurisdiction of the local bishops and placed directly under that of the

Roman Pontiff. This entailed a special bond with the See of Peter and,

thanks precisely to the protection and encouragement of pontiffs, the

ideals of purity and fidelity, which the Cluniac reform intended to

follow, were able to spread rapidly. Moreover, the abbots were elected

without any intervention by the civil authorities, very different to

what was the case in other places. Truly worthy persons succeeded one

another in the guidance of Cluny and of the numerous dependent monastic

communities: Abbot Odilon of Cluny, of whom I spoke in a catechesis two

months ago, and other great personalities, such as Emard, Maiolo, Odilon

and above all Hugh the Great, who carried out their service for long

periods, ensured stability to the reform undertaken and to its

diffusion. Venerated as saints, in addition to Oddon, are Maiolo, Odilon

and Hugh.

The Cluniac reform had positive effects not only on the purification and

reawakening of monastic life, but also on the life of the universal

Church. In fact, the aspiration to evangelical perfection represented a

stimulus to combat two grave evils that afflicted the Church in that

period: simony, that is the acquisition of compensated pastoral offices,

and the immorality of the secular clergy. The abbots of Cluny with their

spiritual authoritativeness, the Cluniac monks who became bishops, some

of them even popes, were protagonists of such an imposing action of

spiritual renewal. And the fruits were not lacking: The celibacy of

priests became esteemed and lived, and more transparent procedures were

introduced in the assumption of ecclesiastical offices.

Significant also were the benefits contributed to society by monasteries

inspired by the Cluniac reform. At a time in which only ecclesiastical

institutions provided for the indigent, charity was practiced with

determination. In all houses, the almoner had to receive passers-by and

needy pilgrims, traveling priests and religious, and above all the poor

who came to ask for food and roof for a day. Not less important were two

other institutions, typical of Medieval civilization, which were

promoted by Cluny: the so-called truce of God and the peace of God. At a

time strongly marked by violence and the spirit of revenge, assured with

the "truce of God" were long periods of non-belligerence, on the

occasion of important religious feasts and of some days of the week.

Requested with "the peace of God," under the pain of a canonical

censure, was respect for defenseless people and sacred places.

Thus enhanced in the conscience of the people of Europe was that process

of long gestation, which led to the recognition, in an ever clearer way,

of two essential elements for the construction of society, that is, the

value of the human person and the primary good of peace. Moreover, as

happened with other monastic foundations, the Cluniac monasteries had

ample properties that, put diligently to good use, contributed to the

development of the economy. Next to manual labor, there was no lack of

some typical cultural activities of Medieval monasticism, such as

schools for children, the setting up of libraries and the scriptoria for

the transcription of books.

In this way, a thousand years ago, when the process of the formation of

European identity was at its height, the Cluniac experience spread over

vast regions of the European Continent, and made its important and

precious contribution. It recalled the primacy of the goods of the

spirit; from this it drew the tension toward the things of God; it

inspired and favored initiatives and institutions for the promotion of

human values; it educated in a spirit of peace.

Dear brothers and sisters, let us pray so that all those who have at

heart a genuine humanism and the future of Europe will be able to

rediscover, appreciate and defend the rich cultural and religious

patrimony of these centuries.

[Translation by ZENIT]

[The Holy Father then greeted the people in several languages. In

English, he said:]

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

In our catechesis on the Christian culture of the Middle Ages, we now

turn to the monastic reform linked to the great monastery of Cluny.

Founded eleven hundred years ago, Cluny restored the strict observance

of the Rule of Saint Benedict and made the Church’s liturgy the centre

of its life. It stressed the solemn celebration of the Liturgy of the

Hours and Holy Mass, and enriched the worship of God with splendid art,

architecture and music. The monastic liturgy, seen as a foretaste of the

heavenly liturgy, was accompanied by a daily regime marked by silence

and intercessory prayer. Cluny’s reputation for sanctity and learning

caused its influence to spread to monasteries throughout Europe. Exempt

from interference by feudal authorities, the monastery freely elected

its abbots and flourished under a series of outstanding spiritual

leaders like Saints Odo and Hugh. Cluny also contributed to the reform

of the universal Church by its concern for holiness, the restoration of

clerical celibacy and the elimination of simony. At a formative time of

Europe’s history, Cluny helped to forge the Continent’s Christian

identity by its emphasis on the primacy of the spirit, respect for human

dignity, commitment to peace and an authentic and integral humanism.

I cordially welcome the English-speaking visitors in attendance at

today’s Audience. I particularly greet pilgrims from the Diocese of Fort

Worth, students and staff from the Franciscan University of

Steubenville, Diocesan Directors of Communications from England and

Wales, as well as priests from Japan. Upon all of you I invoke God’s

blessings of joy and peace!

©Copyright 2009 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

[The Holy Father afterward said in Italian:]

I would now like to greet the young people, the sick and the newlyweds.

Dear young people, especially you beloved students of the St. Therese of

the Child Jesus School of Santa Marinella, consider the example of St.

Martin whose feast we celebrate today, as a model of generous

evangelical witness. You, beloved sick people, trust in the Lord, that

he will not abandon you in in this time of difficulty. And you, beloved

newlyweds, animated by the faith that distinguished St. Martin, always

respect and serve life, which is a gift from God.

[Translation by ZENIT]

Look

at the One they Pierced!

This page is the work of

the Servants of the Pierced Hearts of Jesus and Mary