|

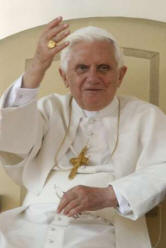

Pope Benedict XVI- General Audiences |

General

Audience

General

Audience

Hugh and Richard, of the Abbey of St. Victor

"Love Alone Makes Us Happy"

H.H. Benedict XVI

November 25, 2009

www.zenit.org

Dear brothers and sisters,

During these Wednesday audiences, I have been presenting some exemplary

figures of believers who have been determined to show the harmony

between reason and faith, and to witness with their life the

proclamation of the Gospel.

Today I would like to speak to you about Hugh and Richard of St. Victor.

Both are among those notable philosophers and theologians known by the

name of Victorines, because they lived in the Abbey of St. Victor in

Paris, founded at the beginning of the 12th century by William of

Champeaux. William himself was a renowned teacher, who was able to give

his abbey a solid cultural identity. In fact, inaugurated in St. Victor

was a school for the formation of monks, open also to outside students,

where a happy synthesis was made between the two forms of doing

theology, of which I have already spoken in previous catecheses: namely,

monastic theology, mainly oriented to the contemplation of the mysteries

of the faith in Scripture, and scholastic theology, which used reason to

attempt to scrutinize these mysteries with innovative methods, to create

a theological system.

We know little about the life of Hugh of St. Victor. The date and place

of his birth are uncertain: perhaps in Saxony or in Flanders. It is

known that he arrived in Paris -- the European capital of culture at the

time -- and spent the rest of his years in the abbey of St. Victor,

where he was first a disciple and then a teacher. Already before his

death, which occurred in 1141, he achieved great notoriety and esteem,

to the point of being called a "second St. Augustine": Like Augustine,

in fact, he meditated much on the relation between faith and reason,

between profane sciences and theology.

According to Hugh of St. Victor, all sciences, in addition to being

useful to understand the Scriptures, have value in themselves and should

be cultivated to enhance man's learning, and also to correspond to his

desire to know the truth. This healthy intellectual curiosity induced

him to recommend to students that they never stifle the desire to learn

and -- in his treatise on the methodology of learning and pedagogy,

titled significantly Didascalicon (on teaching) -- he recommended:

"Learn happily from everyone what you do not know. He will be the wisest

of all who has desired to learn something from all. He who receives

something from everyone, ends us by being the richest of all" (Eruditiones

Didascalicae, 3,14: PL 176,774).

The science that concerns the philosophers and theologians of the

Victorines is, in a particular way, theology, which requires first of

all the loving study of sacred Scripture. To know God, in fact, one

cannot but begin from what God himself has wished to reveal of himself

through the Scriptures. In this connection, Hugh of St. Victor is a

typical representative of monastic theology, totally based on biblical

exegesis. To interpret Scripture, he proposes the traditional

Patristic-Medieval articulation, that is, the historical/literal sense,

first of all, then the allegorical and analogical, and finally the

moral. These are four dimensions of the meaning of Scripture that also

today are being rediscovered, because it is seen that in the text and

the narration is hidden a more profound indication: the thread of faith,

which leads us on high and guides us on this earth, teaching us how to

live. However, while respecting these four dimensions of the meaning of

Scripture, in an original way in relation to his contemporaries, he

insists -- and this is something new -- on the importance of the

historical/literal meaning. In other words, before discovering the

symbolic value, the more profound dimensions of the biblical text, it is

necessary to know and reflect further on the meaning of the history

narrated in Scripture. Otherwise, he warns with an effective example,

the risk is run of being like grammar scholars who ignore the alphabet.

For those who know the meaning of the history described in the Bible,

the human circumstances seem marked by Divine Providence, according to a

well-ordered plan. Thus, for Hugh of St. Victor, history is not the

result of a blind destiny or an absurd case, as it might seem. On the

contrary, the Holy Spirit operates in human history, arousing a

wonderful dialogue of men with God, their friend. This theological view

of history makes evident the surprising and salvific intervention of

God, who really enters and acts in history, almost makes himself part of

our history, but always safeguarding and respecting man's liberty and

responsibility.

For our author, the study of sacred Scripture and its historical/literal

meaning makes possible true and authentic theology, that is, the

systematic illustration of truths, to know their structure, the

illustration of the dogmas of the faith, which he represents in a solid

synthesis in the treatise De sacramentis christianae fidei (The

sacraments of the Christian faith). There is found, among other things,

a definition of "sacrament" that, subsequently perfected by other

theologians, has features that even today are very interesting. "The

sacrament," he writes, "is a corporeal or material element proposed in a

strange and sensible way, which represents with its similarity an

invisible and spiritual grace, it signifies it, because it was

instituted for this purpose, and contains it, because it is capable of

sanctifying" (9,2: PL 176,317). On one hand the visibility of the

symbol, the "corporeal nature" of the gift of God, in which however, on

the other hand, is hidden divine grace that comes from a history: Jesus

Christ himself has created the fundamental symbols. Hence, three are the

elements that concur in the definition of a sacrament, according to Hugh

of St. Victor, the institution on the part of Christ, the communication

of grace, and the analogy between the visible, material element and the

invisible element, which are the divine gifts. It is a vision that is

very close to contemporary sensibility, because the sacraments are

presented with a language interlaced with symbols and images capable of

speaking immediately to men's heart. Also important today is that the

liturgical leaders, and in particular priests, appreciate with pastoral

wisdom the signs themselves of the sacramental rites -- this visibility

and tangibility of grace -- paying careful attention to their

catechesis, so that each celebration of the sacraments is lived by all

the faithful with devotion, intensity and spiritual joy.

A worthy disciple of Hugh of St. Victor is Richard, from Scotland. He

was prior of the Abbey of St. Victor between 1162 and 1173, the year of

his death. Richard also, naturally, assigns an essential role to the

study of the Bible but, as opposed to his teacher, he favors the

allegorical sense, the symbolic meaning of Scripture with which, for

example, he interprets the Old Testament figure of Benjamin, son of

Jacob, as symbol of contemplation and summit of the spiritual life.

Richard treats this argument in two texts. Benjamin minor and Benjamin

major, in which he proposes to the faithful a spiritual way, which first

invites the exercise of the different virtues, learning to discipline

and order with reason the feelings and interior affective and emotional

movements. Only when man has achieved a balance and human maturity in

this field is he prepared to accede to contemplation, which Richard

describes as "a profound and pure look of the soul directed to the

wonders of wisdom, associated to an ecstatic sense of wonder and

admiration" (Benjamin Maior 1,4: PL 196,67).

Contemplation is, therefore, the point of arrival, the result of an

arduous journey, which entails dialogue between faith and reason, that

is -- once again -- a theological discourse. Theology begins from the

truths that are the object of faith, but it attempts to deepen its

knowledge with the use of reason, appropriating the gift of faith. This

application of reasoning to the understanding of faith is practiced in a

convincing way in Richard's masterpiece, one of the great books of

history, the De Trinitate (The Trinity). In the six books that make it

up he reflects with acuity on the mystery of God one and triune.

According to our author, given that God is love, the only divine

substance entails communication, oblation and affection between two

Persons, the Father and the Son, who meet one another with an eternal

exchange of love. But the perfection of happiness and of goodness does

not allow for exclusiveness and narrow-mindedness; on the contrary, it

calls for the eternal presence of a third Person, the Holy Spirit.

Trinitarian love is participatory, harmonious and entails a

superabundance of delight, enjoyment of incessant joy. That is, Richard

assumes that God is love, analyzes the essence of love, which is what is

involved in the reality of love, thus coming to the Trinity of Persons,

which is really the logical expression of the fact that God is love.

Richard, nevertheless, is aware that love, though it reveals God's

essence to us and makes us "understand" the mystery of the Trinity, is,

however, only an analogy to speak about a mystery that exceeds the human

mind, and -- poet and mystic that he is -- he takes recourse also to

other images. For example he compares divinity to a river, to a loving

wave that springs from the Father, flows back in the Son, later to be

happily diffused in the Holy Spirit.

Dear friends, authors such as Hugh and Richard of St. Victor raise our

soul to the contemplation of divine realities. At the same time, the

immense joy we get from thought, admiration and praise of the Most Holy

Trinity, establishes and sustains the concrete commitment to inspire us

in that perfect model of communion and love to build our everyday human

relations.

The Trinity is truly perfect communion! How the world would change if in

families, in parishes and in all other communities relationships were

lived following always the example of the three Divine Persons, where

each one lives not only with the other, but for the other and in the

other! I recalled it some months ago in the Angelus: "Love alone makes

us happy, because we live in relation, and we live to love and to be

loved" (L'Osservatore Romano, June 8-9, 2009, p. 1). It is love that

realizes this incessant miracle: as in the life of the Most Holy

Trinity, plurality is repaired in unity, where everything is pleasure

and joy. With St. Augustine, held in great honor by the Victorines, we

can also exclaim: "Vides Trinitatem, si caritatem vides" -- you see the

Trinity, if you see charity (De Trinitate VIII, 8,12).

[Translation by ZENIT]

[The Holy Father then greeted the people in several languages. In

English, he said:]

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

In our continuing catechesis on the Christian culture of the Middle

Ages, we now turn to two outstanding twelfth-century theologians

associated with the monastery of Saint Victor of Paris. Hugh of Saint

Victor stressed the importance of the literal or historical sense of

sacred Scripture as the basis of theology's effort to unite faith and

reason in understanding God's saving plan. His treatise On the

Sacraments of the Christian Faith offered an influential definition of a

sacrament, stressing not only its institution by Christ and its

communication of grace, but also its value as an outward sign. Richard

of Saint Victor, a disciple of Hugh, stressed the allegorical sense of

the Scriptures in order to present a spiritual paedagogy aimed at human

maturity and contemplative wisdom. Richard's work On the Trinity sought

to understand the mystery of the triune God by analyzing the mystery of

love, which entails a giving and receiving between two persons and finds

its perfection in being bestowed upon a third person. These great

Victorines, Hugh and Richard, remind us that theology is grounded in the

contemplation born of faith and the pursuit of understanding, and brings

with it the immense joy of experiencing the eternal love of the Blessed

Trinity.

I offer a warm welcome to the pilgrimage of Bishops and faithful from

Japan celebrating the first anniversary of the Beatification of Blessed

Peter Kibe and Companions. My cordial greeting also goes to the groups

from Denmark and the United States of America. Upon all the

English-speaking pilgrims and visitors present at today's Audience, I

invoke God's blessings of joy and peace!

ęCopyright 2009 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

[At the conclusion of the audience, the Pontiff gave his customary

greeting in Italian:]

I turn, finally, to young people, the sick and newlyweds. Next Sunday,

the season of Advent begins. I exhort you, young people, to live this

"intense time" with vigilant prayer and generous evangelical commitment.

I encourage you, sick people, to sustain with the offer of your

sufferings the Christian peoples' path of preparation for Holy

Christmas. I hope you, newlyweds, will be witnesses of the Spirit of

love that animates and sustains the whole Family of God.

[Translation by ZENIT]

Look

at the One they Pierced!

This page is the work of

the Servants of the Pierced Hearts of Jesus and Mary