|

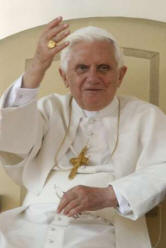

Pope Benedict XVI- General Audiences |

General

Audience

General

Audience

On St. Bernard of Clairvaux

"Faith Is Above All a Personal, Intimate Encounter With Jesus"

H.H. Benedict XVI

October 21, 2009

www.zenit.org

Dear brothers and sisters,

Today I would like to speak about St. Bernard of Clairvaux, called "the

last father" of the Church, because in the 12th century he renewed once

again and rendered present the great theology of the Fathers. We do not

know details about the years of his boyhood. We know, nevertheless, that

he was born in 1090 in Fontaines, France, in a numerous, moderately

comfortable family. As a youth, he spent himself in the study of the

so-called liberal arts -- especially grammar, rhetoric and dialectics --

at the school of the canons of the church of St. Vorles, in

Chatillon-sur-Seine, and he slowly matured his decision to enter the

religious life.

When he was about 20, he entered Citeaux, a new monastic foundation,

more flexible than the old and venerable monasteries of the time and, at

the same time, more rigorous in the practice of the evangelical

counsels. A few years later, in 1115, Bernard was invited by St. Stephen

Harding, third abbot of Citeaux, to found the monastery of Clairvaux.

Here the young abbot -- who was only 25 years old -- was able to refine

his concept of monastic life, and to be determined to put it into

practice. Looking at the discipline of other monasteries, Bernard

decidedly reclaimed the need for a sober and measured life, at table as

well as in dress and in the monastic buildings, recommending the support

and care of the poor. In the meantime, the community of Clairvaux became

ever more numerous and multiplied its foundations.

In those same years, before 1130, Bernard maintained a vast

correspondence with many persons, whether of important or modest social

conditions. To the many letters of this period must be added numerous

sermons, as well as sentences and treatises. Striking at this time was

Bernard's friendship with William, abbot of St. Thierry, and with

William of Champeaux, among the most important figures of the 12th

century.

From 1130 onward, he began to be concerned with not a few grave

questions of the Holy See and of the Church. For this reason, he had to

go out of his monastery ever more often, and sometimes outside of

France. He also founded some women's convents, and was protagonist of a

lively correspondence with Peter the Venerable, abbot of Cluny, about

whom I spoke last Wednesday.

He addressed his controversial writings above all against Abelard, a

great thinker who began a new way of making theology, introducing above

all the dialectic-philosophical method in the construction of

theological thought. Another front against which Bernard fought was the

heresy of the Cathars, who held matter and the human body in contempt,

consequently scorning the Creator. As well, he felt it his duty to take

on the defense of the Jews, condemning the ever more diffuse resurgence

of anti-Semitism. For this last aspect of his apostolic action, some 10

years later, Ephraim, rabbi of Bonn, addressed a vibrant tribute to

Bernard. In that same period the holy abbot wrote his most famous works,

such as the well-known Sermons on the Canticle of Canticles.

In the last years of his life -- his death occurred in 1153 -- Bernard

had to limit his journeys, without however interrupting them altogether.

He took advantage to review definitively the whole of the letters,

sermons and treatises.

Worthy of being mentioned is a book that is quite singular, that he

finished precisely in this period, in 1145, when one of his pupils,

Bernard Pignatelli, was elected Pope, taking the name Eugene III. In

this circumstance, Bernard, in the capacity of spiritual father, wrote

to this spiritual son of his the text "De Consideratione," which

contains teachings on how to be a good pope. In this book, which remains

an appropriate book for popes of all times, Bernard does not only

indicate what it is to be a good pope, but also expresses a profound

vision of the mystery of the Church and of the mystery of Christ, which

is resolved, in the end, in the contemplation of the mystery of the

Triune and One God: "He must again continue the search of this God, who

is not yet sufficiently sought," writes the holy abbot "but perhaps He

can be sought better and found more easily with prayer than with

discussion. We put an end here to the book, but not to the search" (XIV,

32: PL 182, 808), to being on the way to God.

I would now like to reflect on two key aspects of Bernard's rich

doctrine: they regard Jesus Christ and Mary Most Holy, his Mother. His

solicitude for the intimate and vital participation of the Christian in

the love of God in Jesus Christ does not offer new guidelines in the

scientific status of theology. But, in a more than decisive way, the

abbot of Clairvaux configures the theologian to the contemplative and

the mystic. Only Jesus -- insists Bernard in face of the complex

dialectical reasoning of his time -- only Jesus is "honey to the mouth,

song to the ear, joy to the heart (mel in ore, in aure melos, in corde

iubilum)." From here stems, in fact, the title attributed to him by

tradition of Doctor Mellifluus: his praise of Jesus Christ, in fact,

"runs like honey."

In the extenuating battles between nominalists and realists -- two

philosophical currents of the age -- the abbot of Clairvaux does not

tire of repeating that only one name counts, that of Jesus the Nazarene.

"Arid is all food of the soul," he confesses, "if it is not sprinkled

with this oil; insipid, if it is not seasoned with this salt. What is

written has no flavor for me, if I have not read Jesus." And he

concludes: "When you discuss or speak, nothing has flavor for me, if I

have not heard resound the name of Jesus" (Sermones in Cantica

Canticorum XV, 6: PL 183,847).

For Bernard, in fact, true knowledge of God consists in a personal,

profound experience of Jesus Christ and of his love. And this, dear

brothers and sisters, is true for every Christian: Faith is above all a

personal, intimate encounter with Jesus, and to experience his

closeness, his friendship, his love; only in this way does one learn to

know him ever more, and to love and follow him ever more. May this

happen to each one of us."

In another famous sermon on the Sunday Between the Octave of the

Assumption, the holy abbot describes in impassioned terms the intimate

participation of Mary in the redeeming sacrifice of the Son. "O holy

Mother," he exclaims, "truly a sword has pierced your soul! ... To such

a point the violence of pain has pierced your soul, that with reason we

can call you more than martyr, because your participation in the Passion

of the Son greatly exceeded in intensity the physical sufferings of

martyrdom" (14: PL 183, 437-438).

Bernard has no doubts: "per Mariam ad Iesum," through Mary we are led to

Jesus. He attests clearly to Mary's subordination to Jesus, according to

the principles of traditional Mariology. But the body of the sermon also

documents the privileged place of the Virgin in the economy of

salvation, in reference to the very singular participation of the Mother

(compassio) in the sacrifice of the Son. It is no accident that, a

century and a half after Bernard's death, Dante Alighieri, in the last

canto of the Divine Comedy, puts on the lips of the "Mellifluous Doctor"

the sublime prayer to Mary: "Virgin Mary, daughter of your Son,/ humble

and higher than a creature,/ fixed end of eternal counsel, ..." (Paradiso

33, vv. 1ss.).

These reflections, characteristic of one in love with Jesus and Mary as

St. Bernard was, rightly inflame again today not only theologians but

all believers. At times an attempt is made to resolve the fundamental

questions on God, on man and on the world with the sole force of reason.

Instead, St. Bernard, solidly based on the Bible and on the Fathers of

the Church, reminds us that without a profound faith in God, nourished

by prayer and contemplation, by a profound relationship with the Lord,

our reflections on the divine mysteries risk becoming a futile

intellectual exercise, and lose their credibility. Theology takes us

back to the "science of the saints," to their intuitions of the

mysteries of the living God, to their wisdom, gift of the Holy Spirit,

which become the point of reference for theological thought.

Together with Bernard of Clairvaux, we too must recognize that man seeks

God better and finds him more easily "with prayer than with discussion."

In the end, the truest figure of the theologian and of every evangelizer

is that of the Apostle John, who leaned his head on the heart of the

Master.

I would like to conclude these reflections on St. Bernard with the

invocations to Mary that we read in one of his beautiful homilies. "In

danger, in anguish, in uncertainty," he says, "think of Mary, call on

Mary. May she never be far from your lips, from your heart; and thus you

will be able to obtain the help of her prayer, never forget the example

of her life. If you follow her, you cannot go astray; if you pray to

her, you cannot despair; if you think of her, you cannot be mistaken. If

she sustains you, you cannot fall; if she protects you, you have nothing

to fear; if she guides you, do not tire; if she is propitious to you,

you will reach the goal ..." (Hom. II super "Missus est," 17: PL 183,

70-71).

[Translation by ZENIT]

[The Pope then greeted pilgrims in several languages. In English, he

said:]

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

In our continuing catechesis on the theologians of the Middle Ages, we

now turn to one of the most outstanding, Saint Bernard of Clairvaux.

Bernard combined the austerity of the Cistercian monastic renewal with

intense activity in the service of the Church in his time. Because of

his great learning and deep spirituality he is venerated as a Doctor of

the Church, and is often called "the last of the Fathers." Together with

his theological writings and homilies, including the celebrated Sermons

on the Song of Songs, Bernard maintained a vast correspondence,

developed warm friendships with his contemporaries, defended sound

doctrine, and combated heresy and outbreaks of antisemitism. His

spirituality was profoundly Christ-centred and contemplative, and his

celebration of the sweetness of Christ's name won him the title of

Doctor mellifluus. Bernard is also known for his fervent devotion to our

Lady and his insight into her intimate sharing in the sacrifice of her

Son. May Bernard's example of faith nourished by prayer, study and

contemplation, lead us closer "to Jesus through Mary" and grant us that

wisdom which finds joyful fulfillment in the knowledge of the saints in

heaven.

I offer a warm welcome to the English-speaking pilgrims present at

today's Audience, especially from the Diocese of Lismore and Saginaw

accompanied by their Bishops, as well as from Holy Cross and Saint

Margaret Mary parish in Edinburgh. I also greet the visitors from the

Netherlands, Nigeria, Tanzania, England, Ireland, Norway and Sweden.

Upon all of you I invoke God's blessings of peace, joy and hope!

[Copyright 2009 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana]

[In Italian, he said:]

I greet, finally, young people, the sick and newlyweds. Dear friends,

the month of October invites us to renew our active cooperation with the

mission of the Church. With the fresh energies of youth, with the

strength of prayer and of sacrifice and with the capacity of conjugal

life, may you be missionaries of the Gospel, offering your concrete

support to all those who labor, dedicating their whole existence to the

evangelization of peoples.

[Translation by ZENIT]

Look

at the One they Pierced!

This page is the work of

the Servants of the Pierced Hearts of Jesus and Mary