|

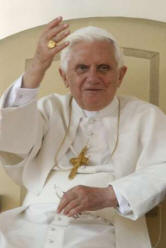

Pope Benedict XVI- General Audiences |

General

Audience

General

Audience

On Theology in the 12th Century

"Knowledge Grows Only if It Loves Truth"

H.H. Benedict XVI

October 28, 2009

www.zenit.org

Dear brothers and sisters,

Today I pause to reflect on an interesting page of history, regarding

the flowering of Latin theology in the 12th century, which came about by

a providential series of coincidences. In the countries of Western

Europe there reigned then a relative peace, which assured society of

economic development and the consolidation of political structures, and

fostered a lively cultural activity thanks also to contacts with the

East. Perceived within the Church were the benefits of the vast action

known as the "Gregorian reform," which, vigorously promoted in the

preceding century, brought greater evangelical purity to the life of the

ecclesial community, above all of the clergy, and restored to the Church

and the papacy genuine liberty of action. Moreover, a vast spiritual

renewal was spreading, sustained by the exuberant development of

consecrated life: New religious orders were being born and spreading,

while those already existing experienced a promising renewal.

Theology was also flourishing, acquiring greater awareness of its own

nature: It refined its method, addressed new problems, advanced in the

contemplation of the mysteries of God, produced fundamental works,

inspired important initiatives of culture -- from art to literature --

and prepared the masterpieces of the next century, the century of Thomas

Aquinas and Bonaventure of Bagnoregio.

There were two realms in which this fervid theological activity

developed: the monasteries and the town schools, the scholae, some of

which very soon gave life to the universities, which constituted one of

the typical "inventions" of the Christian Middle Ages. In fact from

these two realms, the monasteries and the scholae, one can speak of two

different models of theology: "monastic theology" and "scholastic

theology." The representatives of monastic theology were monks, in

general, abbots, gifted with wisdom and evangelical fervor, dedicated

essentially to arousing and nourishing a loving desire for God. The

representatives of scholastic theology were cultured men, passionate

about research; magistri wishing to show the reasonableness and

soundness of the mysteries of God and of man, believed in with faith, of

course, but understood also by reason. The contrasting objectives

explain the differences in their method and their way of doing theology.

In the monasteries of the 12th century the theological method was linked

primarily to the explanation of sacred Scripture, of the sacra pagina,

to express ourselves as the authors of that period did. Biblical

theololy was particularly widespread. The monks, in fact, were all

devoted listeners and readers of sacred Scripture, and one of their main

occupations consisted in lectio divina, namely, prayerful reading of the

Bible. For them the simple reading of the sacred text was not enough to

perceive the profound meaning, the interior unity and the transcendent

message. Therefore, they had to practice a "spiritual reading," leading

in docility to the Holy Spirit. Thus, in the school of the Fathers, the

Bible was interpreted allegorically, to discover in every page, of the

Old as well as the New Testament, what is said about Christ and his work

of salvation.

Last year's synod of bishops on the "Word of God in the Life and Mission

of the Church" recalled the importance of the spiritual approach to

sacred Scripture. To this end, it is useful to treasure monastic

theology, an uninterrupted biblical exegesis, as also the works composed

by its representatives, precious ascetic commentaries on the books of

the Bible. Therefore, to literary preparation, monastic theology joined

spiritual preparation. It was, in fact, aware that a purely theoretic or

profane reading was not enough: To enter the heart of sacred Scripture,

it must be read in the spirit in which it was written and created.

Literary preparation was necessary to know the exact meaning of the

words and to facilitate the understanding of the text, refining the

grammatical and philological sensibility. Jean Leclercq, the Benedictine

scholar of the last century titled the essay with which he presented the

characteristics of monastic theology thus : "L'amour des lettres et le

desir de Dieu" (The love of words and the desire for God).

In fact, the desire to know and to love God, which comes to us through

his Word received, meditated and practiced, leads to seeking to go

deeper into the biblical texts in all their dimensions. There is then

another attitude on which those who practice monastic theology insist,

that is, a profound attitude of prayer, which must precede, support and

complement the study of sacred Scripture. Because, in the last analysis,

monastic theology is listening to the Word of God, one cannot but purify

the heart to receive it and, above all, one cannot but kindle it with

fervor to encounter the Lord. Therefore, theology becomes meditation,

prayer, song of praise and drives one to a sincere conversion. Not a few

representatives of monastic theology reached, along this way, the

highest goal of mystical experience, and they constitute an invitation

also for us to nourish our existence with the Word of God, for example,

through more attentive listening to the readings and the Gospel,

especially in Sunday Mass. Moreover, it is important to reserve a

certain time every day for meditation of the Bible, so that the Word of

God is the lamp that illumines our daily path on earth.

Scholastic theology, instead, -- as I was saying -- was practiced in the

scholae, arising next to the great cathedrals of the age, for the

preparation of the clergy, or around a teacher of theology and his

disciples, to form professionals of culture, at a time in which learning

was increasingly appreciated. Central to the method of the scholastics

was the quaestio, namely the problem posed to the reader in addressing

the words of Scripture and Tradition. In face of the problem that these

authoritative texts pose, questions arose and debate was born between

the teacher and the students. In such a debate appeared, on one hand,

the arguments of authority, and, on the other, those of reason, and the

debate developed in the sense of finding, in the end, a synthesis

between authority and reason to attain a more profound understanding of

the word of God.

In this regard, St. Bonaventure says that theology is "per additionem"

(cf. Commentaria in quatuor libros sententiarum, I, proem., q. 1, concl.),

that is, theology adds the dimension of reason to the word of God and

thus creates a more profound, more personal faith, and therefore also

more concrete in the life of man. In this connection, different

solutions were found and conclusions were formed that began to construct

a system of theology. The organization of the quaestiones led to the

compilation of increasingly extensive syntheses, that is, the different

quaestiones were composed with the answers that ensued, thus creating a

synthesis, the so-called summae, which were, in reality, ample

theological-dogmatic treatises born from the confrontation of human

reason with the word of God.

Scholastic theology sought to present the unity and harmony of Christian

Revelation with a method, called specifically "Scholastic," of the

school, which gives confidence to human reason: grammar and philology

are at the service of theological learning, but so increasingly is

logic, namely that discipline that studies the "functioning" of human

reasoning, so that the truth of a proposition seems evident. Also today,

reading the scholastic summae, one is struck by the order, clarity,

logical concatenation of the arguments, and of the depth of some of the

intuitions. Attributed to every word, with technical language, is a

precise meaning and, between believing and understanding, there is

established a reciprocal movement of clarification.

Dear brothers and sisters, echoing the invitation of the First Letter of

Peter, scholastic theology stimulates us to be always ready to answer

anyone asking for the reason for the hope that is in us (cf. 3:15). To

take the questions as directed to us and thus be capable also of giving

an answer. It reminds us that there is between faith and reason a

natural friendship, founded on the order of creation itself.

The Servant of God John Paul II, in the beginning of the encyclical

"Fides et Ratio," wrote: "Faith and reason are like the two wings, with

which the human spirit soars towards contemplation of the truth." Faith

is open to the effort of understanding on the part of reason; reason, in

turn, recognizes that faith does not mortify it, rather it drives it

toward wider and loftier horizons. Inserted here is the perennial lesson

of monastic theology. Faith and reason, in reciprocal dialogue, vibrate

with joy when both are animated by the search for profound union with

God. When love vivifies the prayerful dimension of theology, knowledge,

acquired by reason, is broadened. Truth is sought with humility,

received with wonder and gratitude: In a word, knowledge grows only if

it loves truth. Love becomes intelligence and theology the authentic

wisdom of the heart, which orients and sustains the faith and life of

believers. Let us pray, therefore, that the path of knowledge and of

deepening in the mysteries of God is always illumined by divine love.

[Translation by ZENIT]

[The Holy Father then greeted pilgrims in several languages. In English,

he said:]

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

In our catechesis on the Christian thinkers of the Middle Ages, we now

turn to the renewal of theology in the wake of the Gregorian Reform. The

twelfth century was a time of a spiritual, cultural and political

rebirth in the West. Theology, for its part, became more conscious of

its own nature and method, faced new problems and paved the way for the

great theological masterpieces of the thirteenth century, the age of

Saint Thomas Aquinas and Bonaventure. Two basic "models" of theology

emerged, associated respectively with the monasteries and the schools

which were the forerunners of the medieval universities. Monastic

theology grew out of the prayerful contemplation of the Scriptures and

the texts of the Church Fathers, stressing their interior unity and

spiritual meaning, centred on the mystery of Christ. Scholastic theology

sought to clarify the understanding of the faith by study of the sources

and the use of logic, and led to the great works of synthesis known as

the Summae. Even today this confidence in the harmony of faith and

reason inspires us to account for the hope within us (cf. 1 Peter 3:15)

and to show that faith liberates reason, enabling the human spirit to

rise to the loving contemplation of that fullness of truth which is God

himself.

I offer a warm welcome to the English-speaking visitors present at

today's Audience, especially those from England, Ireland, Sweden,

Nigeria, India and the United States. My particular greeting goes to the

priests attending a course at the Pontifical North American College and

to the seminarians of the Pontifical Scots College. Upon all of you I

invoke God's blessings of joy and peace!

[Copyright 2009 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana]

[In Italian, he said:]

I greet, finally, young people, the sick and newlyweds. Today the

liturgy remembers the Holy Apostles Simon and Jude Thaddaeus. May their

evangelical testimony sustain you, dear young people, in the commitment

of daily faithfulness to Christ; may it encourage you, dear sick people,

to always follow Jesus on the path of trial and suffering; may it help

you, dear newlyweds, to make of your family the place of constant

encounter with the love of God and neighbor.

[Translation by ZENIT]

Look

at the One they Pierced!

This page is the work of

the Servants of the Pierced Hearts of Jesus and Mary