Mary

Turns to Us, Saying:

Mary

Turns to Us, Saying:

Have the Courage to Dare With God!

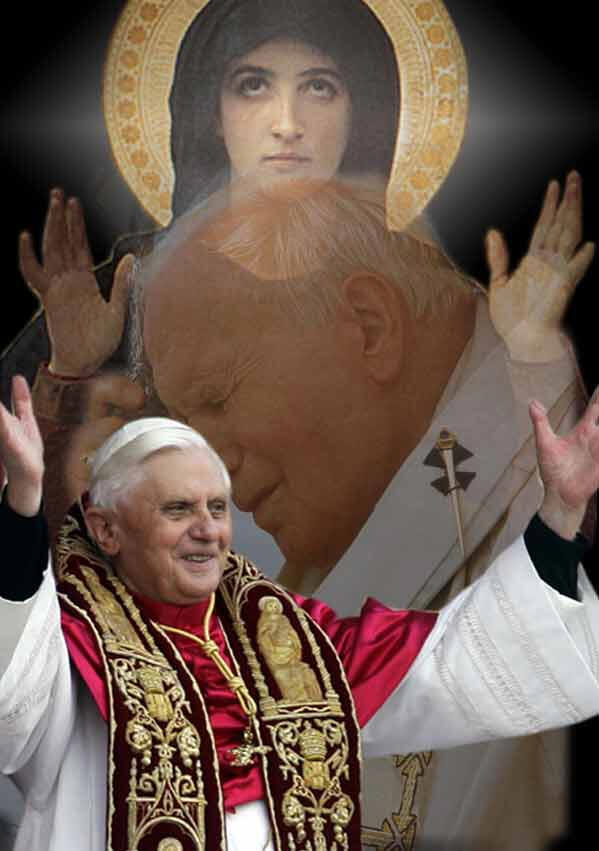

The Petrine and Marian principle

H.H. Benedict XVI

St. Peter's Basilica

Dec. 8, 2005

Papal

Homily on 40th Anniversary of the Close of Vatican II

The Mass was on the solemnity of the Immaculate Conception

Dear Brothers in the Episcopate and in the Priesthood,

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

Pope Paul VI solemnly concluded the Second Vatican Council in

the square in front of St. Peter's Basilica 40 years ago, on 8

December 1965. It had been inaugurated, in accordance with John

XXIII's wishes, on 11 October 1962, which was then the feast of

Mary's Motherhood, and ended on the day of the Immaculate

Conception.

The Council took place in a Marian setting. It was actually far

more than a setting: It was the orientation of its entire

process. It refers us, as it referred the Council Fathers at

that time, to the image of the Virgin who listens and lives in

the Word of God, who cherishes in her heart the words that God

addresses to her and, piecing them together like a mosaic,

learns to understand them (cf. Luke 2:19,51).

It refers us to the great Believer who, full of faith, put

herself in God's hands, abandoning herself to his will; it

refers us to the humble Mother who, when the Son's mission so

required, became part of it, and at the same time, to the

courageous woman who stood beneath the Cross while the disciples

fled.

In his discourse on the occasion of the promulgation of the

dogmatic constitution on the Church, Paul VI described Mary as "tutrix

huius Concilii" -- "Patroness of this Council" (cf. "Oecumenicum

Concilium Vaticanum II, Constitutiones Decreta Declarationes,"

Vatican City, 1966, p. 983) and, with an unmistakable allusion

to the account of Pentecost transmitted by Luke (cf. Acts

1:12-14), said that the Fathers were gathered in the Council

Hall "cum Maria, Matre Iesu" and would also have left it in her

name (p. 985).

Indelibly printed in my memory is the moment when, hearing his

words: "Mariam Sanctissimam declaramus Matrem Ecclesiae" -- "We

declare Mary the Most Holy Mother of the Church," the Fathers

spontaneously rose at once and paid homage to the Mother of God,

to our Mother, to the Mother of the Church, with a standing

ovation.

Indeed, with this title the Pope summed up the Marian teaching

of the Council and provided the key to understanding it. Not

only does Mary have a unique relationship with Christ, the Son

of God who, as man, chose to become her Son. Since she was

totally united to Christ, she also totally belongs to us. Yes,

we can say that Mary is close to us as no other human being is,

because Christ becomes man for all men and women and his entire

being is "being here for us."

Christ, the Fathers said, as the Head, is inseparable from his

Body which is the Church, forming with her, so to speak, a

single living subject. The Mother of the Head is also the Mother

of all the Church; she is, so to speak, totally emptied of

herself; she has given herself entirely to Christ and with him

is given as a gift to us all. Indeed, the more the human person

gives himself, the more he finds himself.

The Council intended to tell us this: Mary is so interwoven in

the great mystery of the Church that she and the Church are

inseparable, just as she and Christ are inseparable. Mary

mirrors the Church, anticipates the Church in her person, and in

all the turbulence that affects the suffering, struggling Church

she always remains the Star of salvation. In her lies the true

center in which we trust, even if its peripheries very often

weigh on our soul.

In the context of the promulgation of the constitution on the

Church, Paul VI shed light on all this through a new title

deeply rooted in Tradition, precisely with the intention of

illuminating the inner structure of the Church's teaching, which

was developed at the Council. The Second Vatican Council had to

pronounce on the institutional components of the Church: on the

bishops and on the Pontiff, on the priests, lay people and

religious, in their communion and in their relations; it had to

describe the Church journeying on, "clasping sinners to her

bosom, at once holy and always in need of purification ..."

("Lumen Gentium," No. 8).

This "Petrine" aspect of the Church, however, is included in

that "Marian" aspect. In Mary, the Immaculate, we find the

essence of the Church without distortion. We ourselves must

learn from her to become "ecclesial souls," as the Fathers said,

so that we too may be able, in accordance with St. Paul's words,

to present ourselves "blameless" in the sight of the Lord, as he

wanted us from the very beginning (cf. Colossians 1:21;

Ephesians 1:4).

But now we must ask ourselves: What does "Mary, the Immaculate"

mean? Does this title have something to tell us? Today, the

liturgy illuminates the content of these words for us in two

great images.

First of all comes the marvelous narrative of the annunciation

of the Messiah's coming to Mary, the Virgin of Nazareth. The

Angel's greeting is interwoven with threads from the Old

Testament, especially from the Prophet Zephaniah. He shows that

Mary, the humble provincial woman who comes from a priestly race

and bears within her the great priestly patrimony of Israel, is

"the holy remnant" of Israel to which the prophets referred in

all the periods of trial and darkness.

In her is present the true Zion, the pure, living dwelling-place

of God. In her the Lord dwells, in her he finds the place of his

repose. She is the living house of God, who does not dwell in

buildings of stone but in the heart of living man. She is the

shoot which sprouts from the stump of David in the dark winter

night of history. In her, the words of the Psalm are fulfilled:

"The earth has yielded its fruits" (Psalm 67:7).

She is the offshoot from which grew the tree of redemption and

of the redeemed. God has not failed, as it might have seemed

formerly at the beginning of history with Adam and Eve or during

the period of the Babylonian Exile, and as it seemed anew in

Mary's time when Israel had become a people with no importance

in an occupied region and with very few recognizable signs of

its holiness.

God did not fail. In the humility of the house in Nazareth lived

holy Israel, the pure remnant. God saved and saves his people.

From the felled tree trunk Israel's history shone out anew,

becoming a living force that guides and pervades the world. Mary

is holy Israel: She says "yes" to the Lord, she puts herself

totally at his disposal and thus becomes the living temple of

God.

The second image is much more difficult and obscure. This

metaphor from the Book of Genesis speaks to us from a great

historical distance and can only be explained with difficulty;

only in the course of history has it been possible to develop a

deeper understanding of what it refers to.

It was foretold that the struggle between humanity and the

serpent, that is, between man and the forces of evil and death,

would continue throughout history. It was also foretold,

however, that the "offspring" of a woman would one day triumph

and would crush the head of the serpent to death; it was

foretold that the offspring of the woman -- and in this

offspring the woman and the mother herself -- would be

victorious and that thus, through man, God would triumph.

If we set ourselves with the believing and praying Church to

listen to this text, then we can begin to understand what

original sin, inherited sin, is and also what the protection

against this inherited sin is, what redemption is.

What picture does this passage show us? The human being does not

trust God. Tempted by the serpent, he harbors the suspicion that

in the end, God takes something away from his life, that God is

a rival who curtails our freedom and that we will be fully human

only when we have cast him aside; in brief, that only in this

way can we fully achieve our freedom.

The human being lives in the suspicion that God's love creates a

dependence and that he must rid himself of this dependency if he

is to be fully himself. Man does not want to receive his

existence and the fullness of his life from God.

He himself wants to obtain from the tree of knowledge the power

to shape the world, to make himself a god, raising himself to

God's level, and to overcome death and darkness with his own

efforts. He does not want to rely on love that to him seems

untrustworthy; he relies solely on his own knowledge since it

confers power upon him. Rather than on love, he sets his sights

on power, with which he desires to take his own life

autonomously in hand. And in doing so, he trusts in deceit

rather than in truth and thereby sinks with his life into

emptiness, into death.

Love is not dependence but a gift that makes us live. The

freedom of a human being is the freedom of a limited being, and

therefore is itself limited. We can possess it only as a shared

freedom, in the communion of freedom: Only if we live in the

right way, with one another and for one another, can freedom

develop.

We live in the right way if we live in accordance with the truth

of our being, and that is, in accordance with God's will. For

God's will is not a law for the human being imposed from the

outside and that constrains him, but the intrinsic measure of

his nature, a measure that is engraved within him and makes him

the image of God, hence, a free creature.

If we live in opposition to love and against the truth -- in

opposition to God -- then we destroy one another and destroy the

world. Then we do not find life but act in the interests of

death. All this is recounted with immortal images in the history

of the original fall of man and the expulsion of man from the

earthly Paradise.

Dear brothers and sisters, if we sincerely reflect about

ourselves and our history, we have to say that with this

narrative is described not only the history of the beginning but

the history of all times, and that we all carry within us a drop

of the poison of that way of thinking, illustrated by the images

in the Book of Genesis.

We call this drop of poison "original sin." Precisely on the

feast of the Immaculate Conception, we have a lurking suspicion

that a person who does not sin must really be basically boring

and that something is missing from his life: the dramatic

dimension of being autonomous; that the freedom to say no, to

descend into the shadows of sin and to want to do things on

one's own is part of being truly human; that only then can we

make the most of all the vastness and depth of our being men and

women, of being truly ourselves; that we should put this freedom

to the test, even in opposition to God, in order to become, in

reality, fully ourselves.

In a word, we think that evil is basically good, we think that

we need it, at least a little, in order to experience the

fullness of being. We think that Mephistopheles -- the tempter

-- is right when he says he is the power "that always wants evil

and always does good" (J.W. von Goethe, "Faust" I, 3). We think

that a little bargaining with evil, keeping for oneself a little

freedom against God, is basically a good thing, perhaps even

necessary.

If we look, however, at the world that surrounds us we can see

that this is not so; in other words, that evil is always

poisonous, does not uplift human beings but degrades and

humiliates them. It does not make them any the greater, purer or

wealthier, but harms and belittles them.

This is something we should indeed learn on the day of the

Immaculate Conception: The person who abandons himself totally

in God's hands does not become God's puppet, a boring "yes man";

he does not lose his freedom. Only the person who entrusts

himself totally to God finds true freedom, the great, creative

immensity of the freedom of good.

The person who turns to God does not become smaller but greater,

for through God and with God he becomes great, he becomes

divine, he becomes truly himself. The person who puts himself in

God's hands does not distance himself from others, withdrawing

into his private salvation; on the contrary, it is only then

that his heart truly awakens and he becomes a sensitive, hence,

benevolent and open person.

The closer a person is to God, the closer he is to people. We

see this in Mary. The fact that she is totally with God is the

reason why she is so close to human beings. For this reason she

can be the Mother of every consolation and every help, a Mother

whom anyone can dare to address in any kind of need in weakness

and in sin, for she has understanding for everything and is for

everyone the open power of creative goodness.

In her, God has impressed his own image, the image of the One

who follows the lost sheep even up into the mountains and among

the briars and thornbushes of the sins of this world, letting

himself be spiked by the crown of thorns of these sins in order

to take the sheep on his shoulders and bring it home.

As a merciful Mother, Mary is the anticipated figure and

everlasting portrait of the Son. Thus, we see that the image of

the Sorrowful Virgin, of the Mother who shares her suffering and

her love, is also a true image of the Immaculate Conception. Her

heart was enlarged by being and feeling together with God. In

her, God's goodness came very close to us.

Mary thus stands before us as a sign of comfort, encouragement

and hope. She turns to us, saying: "Have the courage to dare

with God! Try it! Do not be afraid of him! Have the courage to

risk with faith! Have the courage to risk with goodness! Have

the courage to risk with a pure heart! Commit yourselves to God,

then you will see that it is precisely by doing so that your

life will become broad and light, not boring but filled with

infinite surprises, for God's infinite goodness is never

depleted!"

On this feast day, let us thank the Lord for the great sign of

his goodness which he has given us in Mary, his Mother and the

Mother of the Church. Let us pray to him to put Mary on our path

like a light that also helps us to become a light and to carry

this light into the nights of history. Amen.

[Translation distributed by the Holy See]