Reflection on the

Encyclical of Pope Benedict

XVI:

Caritas in Veritate

"It Is Also Possible

to Do Business by Pursuing Aims That Serve Society"

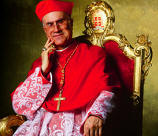

by Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone

Vatican Secretary of State

Address Given to the Italian Senate

July 28, 2009

Benedict XVI begins his

Encyclical with a deep, comprehensive introduction in which he

reflects on and analyzes the words of the title which closely

link "caritas" and "veritas": love and truth. This is not only a

sort of "explicatio terminorum", an initial explanation which

seeks to point out the fundamental principles and perspectives

of his entire teaching. Indeed, like the musical theme of a

symphony, the theme of truth and charity then recurs throughout

the document precisely because, as the Pope writes, in it is

"the principal driving force behind the authentic development of

every person and of all humanity" [1].

But, we ask ourselves, which truth and which love are meant?

There is no doubt that today these very concepts give rise to

suspicion especially the term "truth" or are the object of

misunderstanding, and this is especially the case with the term

"love". This is why it is important to make clear which truth

and which love the Pope is addressing in his new Encyclical. The

Holy Father explains that these two fundamental realities are

neither extrinsic to man nor even imposed upon him in the name

of any kind of ideological vision; rather, they are deeply

rooted within the person. Indeed, "love and truth", the Pope

says, "are the vocation planted by God in the heart and mind of

every human person" [2], the person who, according to Sacred

Scripture, has been created precisely "as an image of the

Creator", in other words of the "God of the Bible, who is both "Agápe"

and "Lógos": Charity and Truth, Love and Word [3].

This reality is testified to us not only by biblical Revelation

but can be grasped by every person of good will who uses right

reason in reflecting on himself [4]. In this regard, several

passages of an important and meaningful Document that came out

just before Caritas in veritate seem to illustrate this view

clearly. The International Theological Commission in recent

months has given us a text entitled "The Search for Universal

Ethics: A New Look at Natural Law". It addresses topics of great

importance which I wish to point out and to recommend especially

in this context of the Senate, that is, an institution whose

main function is legislative. Indeed, as the Holy Father said to

the United Nations Assembly in New York during his Visit last

year to their headquarters [5], sometimes called the "glass

palace", speaking about the foundation of human rights: These

rights "are based on the natural law inscribed on human hearts

and present in different cultures and civilizations. Removing

human rights from this context would mean restricting their

range and yielding to a relativistic conception, according to

which the meaning and interpretation of rights could vary and

their universality would be denied in the name of different

cultural, political, social and even religious outlooks". These

reflections do not apply solely to human rights. They apply to

every intervention by the legitimate authority called to

regulate the life of the community in accordance with true

justice by means of legislation that is not the result of a mere

conventional agreement but aims at the authentic good of the

person and of society and hence refers to this natural law.

Now, expounding on the reality of natural law, the International

Theological Commission describes precisely how truth and love

are essential requirements of every person and are deeply rooted

in his being. "In his search for moral good, the human person

should recognize what he is and be aware of the fundamental

inclinations of his nature" [6], which orient him toward the

goods necessary for his moral fulfilment. As is well known, "a

distinction has traditionally been made between three important

forms of natural dynamism.... The first, in common with every

essential being, is comprised of the fundamental instinct to

preserve and develop one's own existence. The second, which is

shared by all living beings, includes the inclination to

reproduce in order to perpetuate the species. The third, which

is proper to man as a rational being, constitutes the

inclination to know the truth about God and to live in society"

[7]. Examining in depth this third form of dynamism which is

found in every individual, the International Theological

Commission declares that it is "specific to the human being as a

spiritual being, endowed with reason, capable of knowing the

truth, of entering into dialogue with others and of forming

social relationships.... His integral well-being is thus closely

linked to community life, which is organized in a political

society by virtue of a natural inclination and not a mere

convention. The person's relational character is also expressed

in his tendency to live in communion with God or the

Absolute....

Of course, it may be denied by those who refuse to admit the

existence of a personal God, but it remains implicitly present

in the search for truth and for meaning that is present in every

human being" [8].

Man, therefore, through the "breadth of reason" [9], is made to

know the truth in its full depth by "broadening [his] concept of

reason", in other words, not limiting himself to acquiring

technical knowledge in order to dominate material reality but

rather opening himself to the very encounter with the

Transcendent and to living fully the interpersonal dimension of

love, "the principle not only of micro-relationships (with

friends, with family members or within small groups) but also of

macro-relationships (social, economic and political ones)" [10].

"Veritas" and "caritas" themselves point out to us the

requirements of the natural law which Benedict XVI places as a

fundamental criterion for moral reflection on the current

socio-economic reality: "'Caritas in veritate' is the principle

around which the Church's social doctrine turns, a principle

that takes on practical form in the criteria that govern moral

action" [11].

Using a cogent expression, the Holy Father thus affirms that

"the Church's social teaching... is "caritas in veritate in re

sociali": the proclamation of the truth of Christ's love in

society. This doctrine is a service to charity, but its locus is

truth" [12].

What the Encyclical suggests is neither ideological nor

exclusively reserved to those who share belief in the divine

Revelation. Rather, it is based on fundamental anthropological

realities such as, precisely, truth and charity properly

understood or, as the Encyclical itself says, given to the human

being and received by him, but neither planned nor willed by him

[13]. Benedict XVI wants to remind everyone that it is only by

being anchored to this double criterion of "veritas" and

"caritas", inseparably bound together, that it is possible to

build the authentic good of the human being who is made for

truth and love. According to the Holy Father, "only in charity,

illumined by the light of reason and faith, is it possible to

pursue development goals that possess a more humane and

humanizing value" [14].

After this indispensable introduction, of which I have chosen to

highlight some of the anthropological and theological aspects of

the Papal text that may have attracted fewer comments from

journalists, I would now like to explain just a few points,

without claiming to cover the vast content of the Encyclical.

Moreover, authoritative commentators have already published

specific reflections on it in L'Osservatore Romano and

elsewhere.

An important message that comes to us from Caritas in veritate

is the invitation to supersede the now obsolete dichotomy

between the financial sphere and the social sphere. Modernity

has bequeathed to us the idea on the basis of which, if we are

to be able to operate in the field of the economy, it is

essential to achieve a profit and to be motivated chiefly by

self-interest; as if to say that if we do not seek the highest

profit we are not proper entrepreneurs. Should this not be the

case, we must be content with belonging to the social sphere.

This conceptualization, that confuses the market economy that is

the genus with its own particular species which is the

capitalist system, has led to identifying the economy with the

place where wealth or income is generated, and society with the

place of solidarity for its fair distribution.

Caritas in veritate tells us instead that it is also possible to

do business by pursuing aims that serve society and are inspired

by pro-social motives. This is a practical way, if not the only

one, of bridging the gap between the economic and the social

spheres, given that an economic activity which did not

incorporate the social dimension would not be ethically

acceptable. It is likewise true that a social policy concerned

only with redistribution, that failed to reckon with the

available resources, would not be sustainable in the long run:

in fact, production must precede distribution.

We should be particularly grateful to Benedict XVI for wishing

to emphasize the fact that economic action is not separate from

or alien to the cornerstones of the Church's social teaching

such as: the centrality of the human person, solidarity,

subsidariety, the common good.

It is necessary to supersede the current concept which expects

the Church's social teaching and values to be confined to social

activities, while experts in efficiency would be charged with

guiding the economy. It is the merit and certainly not a

secondary one of this Encyclical to contribute to remedying this

gap which is both cultural and political.

Contrary to what people think, efficiency is not the fundamentum

divisionis for distinguishing between what is business and what

is not, for the simple reason that "efficiency" is a category

that belongs to the order of means and not of ends. Indeed,

efficiency is indispensable in order to achieve as well as

possible the purpose one has freely chosen to give one's action.

The entrepreneur who gives priority to efficiency that is an end

in itself risks being caught by one of the most frequent causes

of the destruction of wealth today, as the current economic and

financial crisis sadly confirms.

To expand briefly on this theme, to say "market" means saying

"competition", in the sense that the market cannot exist where

there is no competition (even if the opposite is not true). And

there is no one who can fail to see that the fruitfulness of

competition lies in the fact that it implies tension, the

dialectic that presupposes the presence of another and the

relationship with another. Without tension there is no movement,

but the movement this is the point to which tension gives rise

can also be fatal; in other words it can generate death.

If the purpose of economic action is not synonymous with

striving for a common goal as the Latin etymology "cum-petere"

would clearly indicate but rather with Hobbes' theory, "mors tua,

vita mea" [your death is my life], then the social bond is

reduced to commercial relations and economic activity tends to

become inhuman, hence ultimately inefficient. Therefore, even in

competition, "the Church's social doctrine holds that

authentically human social relationships of friendship,

solidarity and reciprocity can also be conducted within economic

activity, and not only outside it or "after" it. The economic

sphere is neither ethically neutral, nor inherently inhuman and

opposed to society. It is part and parcel of human activity and

precisely because it is human, it must be structured and

governed in an ethical manner" [15].

Well, the advantage by no means small that Caritas in veritate

offers us is to give special consideration to the concept of

market, typical of the tradition of the thought of civil

economics, according to which it is possible to live the

experience of human sociality within a normal economic life and

not outside or beside it. This concept might be defined as an

alternative, both regarding the concept that sees the market as

a place for the exploitation and abuse of the weak by the

strong, and the concept which, in line with

anarchic-liberalistic thought, sees it as a place that can

provide solutions to all the problems of society.

This way of doing business is differentiated from that of the

traditional Smithian economy, which sees the market as the only

institution truly necessary for democracy and freedom. The

Church's social doctrine, on the other hand, reminds us that a

sound society is certainly the product of the market and of

freedom, but there are needs that stem from the principle of

brotherhood that can neither be avoided nor be referred solely

to the private sphere or to philanthropy. Rather, the Church's

social doctrine proposes a humanism with various dimensions, in

which the market is not combated or "controlled" but is seen as

an important institution in the public sphere a sphere which far

exceeds State control which, if it is conceived of and lived as

a place that is also open to the principles of reciprocity and

of giving, can construct a healthy civil coexistence.

I shall now examine one of the themes in the Encyclical which

seems to me to have attracted some public interest because of

the newness of the principles of brotherhood and free giving in

economic activity. "Social and political development, if it is

to be authentically human", Pope Benedict XVI says, needs "to

make room for the principle of gratuitousness" [16]. "Internal

forms of solidarity" are essential. The chapter on the

cooperation of the human family is significant in this regard.

In it the Pope stresses that "the development of peoples

depends, above all, on a recognition that the human race is a

single family", which is why "thinking of this kind requires a

deeper critical evaluation of the category of relation". And

further: "The theme of development can be identified with the

inclusion-in-relation of all individuals and peoples within the

one community of the human family, built in solidarity on the

basis of the fundamental values of justice and peace" [17].

The key word that today expresses this need better than any

other is "brotherhood". It was the Franciscan school of thought

that gave this term the meaning it has retained over the course

of time and that constitutes the complement and exaltation of

the principle of solidarity. In fact, whereas solidarity is the

principle of social organization that permits those who are

unequal to become equal through their equal dignity and their

fundamental rights, the principle of brotherhood is that

principle of social organization which permits equals to be

different, in the sense that they are able to express their plan

of life or their charism in different ways.

Let me explain more clearly. The periods we have left behind us,

the 19th century and especially the 20th century, were marked by

great battles both cultural and political in the name of

solidarity. This was a good thing; only think of the history of

the trade union movement and of the fight to obtain civil

rights. The point is that a society oriented to the common good

cannot stop at solidarity because it needs a solidarity that

reflects brotherhood, given that while a fraternal society also

shows solidarity, the opposite is not necessarily true.

If one overlooks the unsustainability of a human society in

which the sense of brotherhood is lacking and in which

everything revolves around improving transactions based on the

exchange of equivalents or to increasing transfers actuated by

public structures for social assistance it then becomes clear

why, in spite of the quality of the intellectual forces at work,

we have not yet found a credible solution to the great trade-off

between efficiency and equity. Caritas in veritate helps us to

realize that society can have no future if the principle of

brotherhood is lost. In other words, society cannot progress if

the logic of "giving in order to have" or of "giving as a duty"

is the only one that exists and develops. This is why neither

the liberal-individualistic vision of the world, in which

(almost) everything is exchange, nor the State-centred vision of

society, in which (almost) everything is based on obligation,

are reliable guides to lead us out of the shallows in which our

societies today have run aground.

Then we ask ourselves the question: why is the perspective of

the common good as it has been formulated by the Church's social

doctrine, which was banished from the scene for at least two

centuries, re-emerging like an underground river? Why is the

transition from national markets to the global market that has

taken place over the last 25 years rendering the topic of the

common good timely once again? I note in passing that what is

occurring is part of a broader movement of ideas in economics, a

movement whose goal is the link between a religious sense and

economic performance. On the basis of the consideration that

religious beliefs are of crucial importance in forging people's

cognitive maps and in shaping the social norms of behaviour,

this movement of ideas is seeking to investigate how far the

prevalence in a specific country (or territory) of a certain

religious matrix influences the formation of categories of

economic thought, welfare programmes, educational policies and

so forth. After a long period, during which the celebrated

theses of secularization appeared to have had the last word on

the religious question at least insofar as the economic field is

concerned what is happening today appears truly paradoxical.

It is not difficult to explain the return to the contemporary

cultural debate in the perspective of the common good, a true

and proper symbol of Catholic ethics in the social and economic

field. As John Paul ii explained on many occasions, the Church's

social teaching should not be considered as yet another ethical

theory as regards the numerous theories already available in

literature. Instead it should be seen as their "common grammar",

since it is based on a specific viewpoint, the preservation of

the human good. In truth, while the various ethical theories are

rooted either in the search for rules (as happens in the

positivist doctrine of natural law), or in action (as in Rawls'

neo-contractualism or neo-utilitarianism), the social doctrine

of the Church embraces "being with" as its Archimedean point.

The ethical sense of the common good explains that in order to

understand human action we must see it from the perspective of

the acting person [18] and not from the viewpoint of the third

person (as does natural law) or of the impartial spectator (as

Adam Smith had suggested). In fact since the moral good is a

practical reality, it is known first and foremost by those who

practise it rather than by those who theorize about it. They can

identify it and hence choose it unhesitatingly every time it is

questioned.

Next, let us speak of the principle of free giving in the

economy. What would be the practical consequence of applying the

principle of free giving in economic activity? Pope Benedict XVI

replies that the market and politics need "individuals who are

open to reciprocal gift" [19]. The consequence of acknowledging

that the principle of gratuitousness has a priority place in

economic life has to do with the dissemination of culture and of

the practice of reciprocity.

Together with democracy, reciprocity defined by Benedict XVI as

"the heart of what it is to be a human being" [20] is a founding

value of a society. Indeed, it could also be maintained that

democratic rule draws its ultimate meaning from reciprocity.

In what "places" is reciprocity at home? In other words, where

is it practised and nourished? The family is the first of these

places: only think of the relationships between parents and

children and between siblings. It is in the context of one's

family that the relationship characteristic of brotherhood and

based on giving develops. Then there are the cooperative, the

social enterprise and associations in their various forms. Is it

not true that the relationship between family members or the

members of a cooperative are relations of reciprocity? Today we

know that a country's civil and economic progress depends

fundamentally on the extent to which reciprocity is practised by

its citizens. Today there is an immense need for cooperation:

this is why we need to extend the forms of free giving and to

reinforce those that already exist. Societies that uproot the

tree of reciprocity from their land are destined to decline, as

history has been teaching us for years.

What is the proper role of the gift? It is to make people

understand that beside the goods of justice are the goods of

gratuitousness and, consequently, that the society whose members

are content with the goods of justice alone is not authentically

human. The Pope speaks of "the astonishing experience of gift"

[21].

What is the difference? The goods of justice are those that

derive from a duty. The goods of giving freely are those that

are born from an obbligatio. That is, they are goods born from

the recognition that I am bound to another and that, in a

certain sense he is a constitutive part of me. This is why the

logic of gratuitousness cannot be simplistically reduced to a

purely ethical dimension. Indeed, gratuitousness is not an

ethical virtue. Justice, as Plato formerly taught, is an ethical

virtue, and we are all in agreement as to the importance of

justice; but gratuitousness concerns rather the supra-ethical

dimension of human action because its logic is superabundance,

whereas the logic of justice is the logic of equivalence. Well,

Caritas in veritate tells us that to function well and to

progress, a society needs to have in its economic praxis people

who understand what the goods of gratuitousness entail, in other

words, who understand that we must let the principle of

gratuitousness circulate anew in the channels of our society.

Benedict XVI asks us to restore the principle of gift to the

public sphere. The authentic gift affirming the primacy of

relationship over its reciprocation, of the inter-subjective

bond over the good that is given, of personal identity over

assets must find room for expression everywhere, in every

context of human action, including the economy. The message that

Caritas in veritate offers us is to think of gratuitousness

hence brotherhood as a symbol of the human condition and thus to

see the practice of giving as the indispensable prerequisite for

the State and the market to function, with the common good as

their goal. Without the widespread practice of giving, it would

still be possible to have an efficient market and an

authoritative (and even just) State, but people would certainly

not be helped to achieve joie de vivre. Because, even if

efficiency and justice are combined, they are not enough to

guarantee people's happiness.

In Caritas in veritate Pope Benedict XVI reflects on the

profound (and not on the immediate) causes of the current

crisis. It is not my intention to review them and I shall limit

myself to summing up the three principal factors of the crisis,

identified and examined.

The first concerns the radical change in the relationship

between finance and the production of goods and services which

has gradually been consolidated in the past 30 years. From the

mid-1970s various Western countries have based their promises of

pension funds on investments that depended on the sustainable

profitability of the new financial instruments, thereby exposing

the real economy to the caprices of finance and generating the

growing need to earmark value-added quotas to the remuneration

of savings invested in these. The pressure on businesses

deriving from stock exchanges and private equity funds have had

repercussions in various directions: on directors, obliged to

continuously improve the performance of their management in

order to receive a growing number of stock options; on

consumers, to convince them to buy more and more, even in the

absence of purchasing power; on businesses of the real economy

to convince them to increase the value for the shareholder.

And so it was that the persistent demand for increasingly

brilliant financial results had repercussions on the entire

economic system, to the point that it became a true and proper

cultural model.

The second factor that contributed to causing the crisis was the

dissemination in popular culture of the ethos of efficiency as

the ultimate criterion of judgement and the justification of the

financial reality. On the one hand, this ended by legitimizing

greed which is the best known and most widespread form of

avarice as a sort of civic virtue: the greed market that

replaces the free market. "Greed is good, greed is right",

preached Gordon Gekko, who starred in Wall Street, the famous

1987 film.

Lastly, in Caritas in veritate the Pope does not omit to reflect

on the cause of the causes of the crisis: the specificity of the

cultural matrix that was consolidated in recent decades on the

wave of the globalization process on the one hand, and on the

other, with the advent of the third industrial revolution, the

revolution of information technology. One specific aspect of

this matrix concerns the ever more widespread dissatisfaction

with the way of interpreting the principle of freedom. As is

well known, there are three constitutive dimensions of freedom:

autonomy, immunity, and empowerment.

Autonomy means freedom of choice: one is not free unless one is

in a position to choose. Immunity, on the other hand, means the

absence of coercion by some external agent. It is substantially

negative freedom (in other words it is "freedom from"). Lastly,

empowerment (literally: the capacity for action) means the

capacity to choose, that is, for achieving the objectives, at

least in part or to some extent, that the person has set

himself. One is not free even if one succeeds (even only

partially) in realizing one's plan of life.

As can be understood, the challenge is to bring together all

three dimensions of freedom: this is the reason why the paradigm

of the common good appears as a particularly interesting

perspective to explore.

In the light of what has been said above, we can understand why

the financial crisis cannot claim to be an unexpected or

inexplicable event. This is why, without taking anything from

the indispensable interventions in a regulatory key or from the

necessary new forms of control, we shall not succeed in

preventing similar episodes from arising in the future unless

the evil is attacked at the root, or in other words, unless we

intervene by dealing with the cultural matrix that supports the

economic system. This crisis sends a double message to the

Government authorities. In the first place, that the sacrosanct

criticism of the "intervening State" can in no way ignore the

central role of the "regulatory State". Secondly, that the

public authorities at different levels of government, must

allow, indeed enhance, the emergence and reinforcement of a

pluralist financial market. A market, in other words, should

allow different people to work in conditions of objective parity

to achieve the specific aim they have set themselves. I am

thinking of the regional banks, of cooperative credit banks,

ethical banks, of various ethical foundations. These are bodies

that not only propose creative finance to their branches but

above all play a complementary, hence balancing, role with

regard to the agents of speculative finance. If in recent

decades the financial authorities had removed the many

restrictions that burden agents in alternative finance, today's

crisis would not have had the devastating power that we are

experiencing.

Before concluding, I would like to thank Hon. Mr Renato Schifani,

President of the Senate of the Italian Republic, for permitting

me to explain to this qualified audience several features of

Benedict XVI's latest Encyclical.

In a certain way it is as if today the Holy Father were

returning to the Headquarters of the Senate of the Republic,

where, in the Library of the Senate on 13 May 2004, the

then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger gave an unforgettable "lectio

magistralis" on the theme: "Europe. Its spiritual foundations

yesterday, today and tomorrow".

It is interesting to note how, in that discourse, among other

things the future Pontiff touched on certain topics that we

rediscover today in his most recent Encyclical. Let us think,

for example, of the affirmation of the profound reason for the

dignity of the person and of his rights: "they are not created

by the legislator", the then- Cardinal Ratzinger said, "nor are

they conferred upon citizens, "but rather they exist through

their own law, they are always to be respected by the

legislator, they are given to him in advance as values of a

superior order". This validity of human dignity prior to any

political action and any political decision refers ultimately to

the Creator; he alone can establish values that are based on the

essence of the human being and are intangible. That there are

values that cannot be manipulated by anyone is the true and

proper guarantee of our freedom and of human greatness; the

Christian faith sees in this the mystery of the Creator and of

the condition of the image of God who has conferred them on

man". In Caritas in veritate Benedict XVI repeats that "human

rights risk being ignored" when "they are robbed of their

transcendent foundation" [22], that is, when people forget that

"God is the guarantor of man's true development, inasmuch as,

having created him in his image, he also established the

transcendent dignity of men and women" [23].

Further, in the "lectio magistralis" given five years ago, the

current Pontiff recalled that "a second point in which the

European identity appears is marriage and the family. Monogamic

marriage, as a fundamental structure of the relationship between

a man and a woman and at the same time as a cell in the

formation of the State community, was forged on the basis of

biblical faith. It has given its special features and its

special humanity to Western and Eastern Europe, also and

precisely because the form of fidelity and renunciation outlined

here must always be acquired anew, with great effort and much

suffering.

Europe would no longer be Europe if this fundamental cell of its

social edifice were to disappear or to be essentially altered".

In Caritas in veritate this warning is extended until it becomes

universal, we might say global, and reaches all who are

responsible for public life; we read in it, in fact: "It is thus

becoming a social and even economic necessity once more to hold

up to future generations the beauty of marriage and the family,

and the fact that these institutions correspond to the deepest

needs and dignity of the person. In view of this, States are

called to enact policies promoting the centrality and the

integrity of the family founded on marriage between a man and a

woman, the primary vital cell of society, and to assume

responsibility for its economic and fiscal needs, while

respecting its essentially relational character" [24].

Of course, Caritas in veritate is addressed, as it says in its

official title, to all the members of the Catholic Church and to

"all people of good will". Yet, because of the principles it

illumines, the problems it tackles and the guidelines it offers,

it seems to me that this Papal Document which gave rise to so

many expectations beforehand and then to so much attention and

appreciation, especially in the social, political and economic

contexts can find a special echo in this institutional

Headquarters of the Senate of the Republic. I am convinced that,

over and above differences in training and in personal

conviction, those who have the delicate and honourable

responsibility of representing the Italian people and of

exercising legislative power during their mandate, may find in

the Pope's words a lofty and profound inspiration for carrying

out their mission so as to respond adequately to the ethical,

cultural and social challenges which call us into question today

and which, with great lucidity and completeness, the Encyclical

Caritas in veritate sets before us. My hope is that this

document of the ecclesial Magisterium which I have endeavoured

to describe to you today, at least in part, may find here the

attention it deserves and thus bear positive and abundant fruit

for the good of every person and of the entire human family,

starting with the beloved Italian Nation.

--- --- ---

Notes

[1] Caritas in veritate, n. 1

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., n. 3.

[4] "Truth is the light that gives meaning and value to charity.

That light is both the light of reason and the light of faith,

through which the intellect attains to the natural and

supernatural truth of charity" (ibid.).

[5] Discourse to the General Assembly of the United Nations

Organization, 18 April 2008.

[6] The Search for Universal Ethics: A New Look at Natural Law,

n. 45.

[7] Ibid., n. 46.

[8] Ibid., n. 50.

[9] Discourse to the University of Regensburg, 12 September

2006.

[10] Caritas in Veritate, n. 2

[11] Ibid., n. 6.

[12] Ibid., n. 5.

[13] "Truth which is itself a gift, in the same way as charity

is greater than we are, as St Augustine teaches. Likewise the

truth of ourselves, of our personal conscience, is first of all

given to us. In every cognitive process, truth is not something

that we produce, it is always found, or better, received. Truth,

like love, 'is neither planned nor willed, but somehow imposes

itself upon human beings'" (Caritas in Veritate, n. 34).

[14] Ibid., n. 9.

[15] Ibid., n. 36.

[16] Ibid., n. 34.

[17] Ibid., nn. 53-54.

[18] Cf. Veritatis Splendor, n. 78.

[19] Cf. ibid., nn. 35-39.

[20] Ibid., n. 57.

[21] Ibid., n. 34.

[22] Ibid., n. 56.

[23] Ibid., n. 29.

[24] Ibid., n. 44.

© Innovative Media, Inc.