Index:

The Suffering of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the Infancy and Passion of Her Son

Actual Situation in the Doctrine and in the Liturgy

The Doctrine

The Liturgy:

a) September 15: Our Lady of Sorrows, Memorial

b) Paschal Triduum

c) Pious Excercises

d) Popular Devotions

Historical Note

Conclusion

Also See:

The Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

The Way of the Cross of the Sorrowful Mother

I. The Suffering of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the Infancy and Passion of Her Son:

The mystery of the participation of the Blessed Virgin Mary Sorrowful Mother in the passion and death of her Son is probably the event of the Gospel that has found a wide and intense resonance in popular devotion, in certain pious exercises (Way of the Cross, Via Matris..) and, in proportion to the other mysteries, also in the Christian liturgy of the east and west. It is interesting how these three dimensions of piety are ideally united in the liturgy of the roman rite on Stábat Mater, attributed to Jacopone de Todi, a sequence born in an context of intense popular devotion, used in various forms in pious exercises, and, although in an optional form, present in the liturgy of the hours and in the liturgy of the word of the Mass of September 15 of Our Lady of Sorrows. This singularity reveals the three areas of piety that we have mentioned, leaving out certain occasional immoderations, intensely reflect the essential mystery of the Gospel.

The sorrows of the Blessed Virgin Mary, though it finds in the mystery of the cross its first and last meaning, was also perceived by marian piety in other events in the life of her Son in which the Mother participated personally. In general, the sorrows of the Virgin Mary are contemplated in the infancy of Jesus and not only in His passion. Christian meditation captured and in a certain way categorized progressively through the centuries certain sorrowful events, seven Biblical episodes in which the participation of the Blessed Virgin Mary is clearly attested to or perceived by tradition.

We remember Joseph and Mary going up to the temple for the presentation of Jesus after forty days of His birth, in reference "and you yourself a sword will pierce” (Luke 2:34-35). A sword, which “seems to be as progressively revealed by God the fate of her Son”; a sword that as it penetrates Mary will cause her sorrow; sword that is a symbol of the dolorous way of the Blessed Virgin Mary, that in tradition is assumed as a concrete sign of the sorrows suffered by the Mother of the redeemer and represented later as seven swords pierced in the heart of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

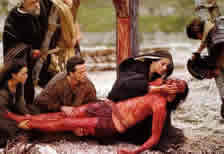

The way of faith of the Blessed Virgin Mary was soon marked by a new sorrowful event: the fleeing to Egypt with Jesus and Joseph (Matthew 2:13-14). Once again, during the infancy of Jesus, the event of Jesus being lost in Jerusalem and the anxious seeking of the sorrowful Virgin Mary and Joseph (Luke 2:43), that concludes in the finding of the Son at the temple, new motive of meditation and interpretation regarding the will of God in the heart of the Mother. The contemplation of tradition has wanted to discover in Jesus carrying His cross up to Calvary the united experience of the way of faith of the Mother, and although the Gospels do not mention this, traditional devotion sees the presence of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the encounter of Jesus with the women (Luke 23, 26-27). As it has been said, it is in the event of the crucifixion where we find the first and last meaning of the sorrowful mother: “Standing by the cross of Jesus were his mother and his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary of Magdala. and the disciple there whom he loved, he said to his mother, “Woman, behold, your son.” (John 19: 25-27a). Once more the devotion of the faithful wanted to prolong the loving participation of the Mother in the redeeming death of her Son remembering how, as in a depiction, the Blessed Virgin Mary embraced in her mantle the body of Jesus as it was taken down from the cross (Mark 15:42), event that has been object of particular attention of sculptors and painters, and also placing the dead body of her Son in the tomb (John 19: 40-42a)

The ancient and contemporary distribution of the aspects of the sorrows of Mary of Nazareth, more than the distribution of the mysteries that took place in other centuries that were venerated separately, in the theological sensibility of our time and also, as it seems in the piety of the faithful, it is not perceived as a division of unrelated events, but rather in the specifications of the

diverse episodes, the sorrows relate harmoniously with the path of a mystery of faith that knew suffering, in total communion with the Man of Sorrows and open to the will of God the Father. We have an authorized summary of this new mentality in the magisterium of Vatican II: “Also the Blessed Virgin Mary advanced in her pilgrimage of faith and remained faithful in her communion with her Son until the Cross, before which she resisted standing (John 19:25), with divine intervention, suffering profoundly with her only begotten Son and uniting to His sacrifice with maternal courage, lovingly consenting the sacrifice of the victim which she had given” (Lumen Gentium 58). In reality it is the profound communion, which in a certain way is made visible, between the mother and the Son, a communion not only associated with generation, but also faith, which allowed the Blessed Virgin Mary to cooperate in the work of Jesus until Calvary: “conceiving Christ, giving Him birth, nourishing him, presenting Him to the Father in the temple, suffering with her dying Son on the cross, she cooperated in a special way in the work of the Savior, with obedience, faith, hope, and ardent charity to restore the supernatural life of souls” (LG 61).

Due to this loving and total participation, the Blessed Virgin Mary becomes “for us our mother in the order of grace” (LG 61). The council’s teaching in fact has abandoned the more delicate problems and the ontological objections, explaining the marian doctrine of the papal encyclicals that had taken care of these topics with biblical and existential data. The investigation has followed this same line of thought, especially by using the profound interpretative that highlights the Blessed Virgin Mary at the foot of the cross, as daughter of Zion, as figure of mother church in whose womb all are invoked to unite the disperse children of God, with its relative consequences, and as in the passion according to John - consisting in such elevated theological heights – Jesus is a man of suffering, knowing pain (Isaiah 53:3), He who was pierced (John 19:37; Zechariah 12:1). At the same time His mother is the woman of suffering… She is clearly also the model of perfect union with Jesus to the cross. One of the most arduous tasks of Christian love is precisely to be near the cross, our own and that of others, it requires that we rejoice with those who rejoice (Romans 12:15; John 2:1 – wedding of Cana) and to weep with those who weep (Romans 12:15; John 19:25: The cross of Jesus)”.

This exemplariness of the Blessed Virgin Mary acquires new aspects of deepening in the reflections of an episcopate such as that of South America: "It is clearly manifested in the Blessed Virgin Mary that Christ does not annul the creativity of those who follow her. Associated with Christ, she carries out all of her human capacities and responsibilities, until she comes to be the new Eve next to the new Adam. The Blessed Virgin Mary by her free cooperation in the new covenant of Christ is with Him a protagonist of history.” The mystery of the mater dolorosa, read in relation to Christ and with the church, becomes a vital experience for the Christian not only in respect to the knowledge of salvation history, but also as a singular fountain of comfort and of hope for daily life.

a) September 15: Our Lady of Sorrows, Memorial

In the apostolic Exhortation Marianis Cultus, Paul VI, after highlighting the presence of the mother in the annual cycle of the mysteries of the Son and of the great marian feasts, presented in this manner the memorial of September 15: “After these solemnities it should be considered, above all, the celebrations that commemorate the salvific events, in which the Virgin was closely bound to her Son, for example the memorial of Our Lady of Sorrows (September 15), perfect occasion to relive a decisive moment in the history of salvation and to venerate together with the Son exalted on the cross the mother who shared His suffering”.

On the day after the feast of the exaltation of the Holy Cross, the church celebrates the compassion of she who remained faithful at the foot of the cross. This memory has its own formula (pieces of scripture and euchology texts) for the Eucharistic celebration and for the proper parts of the liturgy of the hours. The content of the collect prayer can help us to capture the meaning of this celebration: the Christological character of the first part (the action gratiarum) and the ecclesiologic of the second (the petitio) immediately place the memorial of September 15 in a solid theological horizon of wide councilor vision. “O God, who willed that, when your Son was lifted high on the Cross, his Mother should stand close by and share his suffering.” The beginning of the prayer praises the Father and gives Him thanks, because at the hour of redemption He willed that the mother of His Son be present and participate in His work. It is a clear reference to the Gospel of John (19, 25; 3,14-15; 8,28; 12,32) those brief initial phrases give to it the light of the resurrection that the evangelist wanted to pour out on the passion and death of Christ: the cross, besides being an instrument of pain and suffering, is above all a throne of glory. The Mother participates of this light. In effect, the liturgy of September 15 imprints a glorious nature to the mystery of Mary’s suffering (acclamation to the Gospel, communion antiphon, Benedictus antiphon, vespers antiphon and the short reading).

In this manner two great themes of John are summarized harmoniously: the exaltation (3,14-15; 8,28; 12,32) and the hour of Jesus (7,30; 8,20; 12,20-28; 13,1; 16,13-14). The presence of the Blessed Virgin Mary finds for both themes its proper place, the place willed by God. In the collect prayer this presence is highlighted by the noun mater in relation to the Filius: the hour of the exaltation of the cross of Christ is the focal point of the three-part-work “Cana-Calvary-Revelation 12),” where you can see with all clarity that the Virgin is Mother. In Cana (John 2,1-11) she anticipates as mother the inauguration of the mystery of her Son, inviting Him to accomplish the first of the “miracles”: origin of the faith in the disciples, whom she gathers around her to then focus on Christ (John 2:12). At the same time the Blessed Virgin Mary anticipates with this prophetic sign, that hour that displayed in all its light when the Son of man reigned from the wood and poured out His salvation on all of humanity. Also, at that hour, in which the Son disregarded His mother (John 2:4), the Virgin revealed herself as mother of all, as mother of the church (in this sense we must read the prayer over the offerings).Once more the mother is next to Christ in faith, the disciples and all mankind as brothers and sisters are being represented in faith by John. In this faith, against all hope, the Blessed Virgin Mary profoundly experiences the co-participation in the sufferings of the Son (the term in Latin from the “editio typical” of the Roman Missal is “compatientem”, de “pati-cum”, translated sometimes improperly to “sorrowful”; the same can be said of the prayer after communion, where "compassionem B. M.V. recolentes” is translated to: “in remembering the sorrows of the Blessed Virgin Mary.” Not only as mother is she intimately united to the suffering and pain of Christ, but as we have already observed, she is as a blessed believer that sees the foundations of her faith being teased with the passion and death. At the same time she battles the suffering, hoping only in the one who is dying. Then spontaneously the memory of Simeon surges, he prophesied already in that sense: “A sword will pierce your soul” (Luke 2:35), of which we see an echo in the initial antiphon of the Mass in the second passage of the gospel ad líbitum, meaning Luke 2,33-35, and in the second reading of the liturgy of the hours taken from the sermons of Saint Bernard), and the memory of her life of faith that had been preparing her for this reality: admirable expression of the authentic and faithful fruits, that even amidst the suffering she hopes only in He who died and rose. In Revelation 12 there seems to be a clear reference to John 19:25-27. In reference to “woman”, we know that the commentators are divided. However, we believe that the interpretation seen in this woman is not far from the church or from Mary: in effect, “the church and Mary are within themselves complementary realities; they are both irreplaceable complements of the same Christ.” The mother of the Son of God participates with Him, in the hour of history, at the sorrowful generation of all the living, defeating the enemy of the Son of men and participating in His glorification through this victory. In this Biblical sense “viventium mater” (Genesis 3:20) is the perfect title of the New Eve. Spiritual and human Mother of Christ the head, spiritual mother of all the members, of all men and women. This mother is the first that offers her personal collaboration to complete the passion of Christ in favor of the Church, just as Mystici Córporism expressed referring to Colossians 1:24. The liturgy, in the prayer after communion, suggests that as a final fruit this may also be the desire of the assembly that has celebrated the memory of the Sorrowful mother. In this manner the mother becomes for the ecclesia, which continues even now to battle the dragon, waiting for the final glory, a sign of certain hope and source of encouragement.

The petition of the ecclesia is essential: participate in the passion of Christ with His mother and image, yearning ardently to arrive as she did to the final glory: “Make that the church, uniting herself with Mary to the passion of Christ, be worthy to participate in His resurrection.” We are in the heart of the liturgy of September 15, the authentic Christian dimension and the last and most deep sense of the celebration, the same motives that appear in Stábat Mater. What we can glimpse at the beginning of the collect prayer finds its petition as a result in the second part: passion of her Son and of the mother. These two petitions request for the essentials for the life of the church. They respect what is already and what is yet to be. St. Paul helps us to deepen in our sense of these petitions. The total communion with Christ our Lord gives us guarantee to participate in his divine life (see also the antiphons for lauds and vespers). The spirit that he has obtained for us “gives witness together with our spirit of being children of God. Yes children, also heirs: heirs of God, and co-heirs of Christ” (Romans 8, 1-17). Christ freely wanted to show the way for man participating in all and for all in our human life, living in a concrete period events, joys, sufferings, living the depths of death for life. This communion with Him, to be co-heirs with Him, just as the Virgin Mary also lived, supposes that we assume, illumined consciously by faith, the daily life, in which the proper limit of man, suffering, is not an accessory element: (Romans 8:17). The participation of the passion has two perspectives: personal and communal. It is a continual desire to be free of all form of sin, of evil, individual and social. To take up daily our own cross (Luke 9:39) and to compassionately alleviate the cross of any man or woman we find on our path and of the humanity that we are part of (Luke 10, 25-37; John 13, 34). But this passion is not an end to itself, but rather it is for life: “unless a grain of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains just a grain of wheat; but if it dies, it produces much fruit.” (John 12:24); “we suffer with him so that we may also be glorified with him.” (Romans 8:17); “If we have died with him” (2 Timothy 2:11). It is regarding the eschatological tension to the life of all Christian existence. Regarding the hope, that sustains the church now, while she walks to the yet to be. Hope that centers itself, especially in the resurrection of Christ, the first of all the living (Romans 8:18-30).A serene meditation and Reading of the presence of the Blessed Virgin Mary through the liturgical year has arrived to the agreement that in the paschal tridium of the roman liturgy the participation of the mother in the passion of the Son, although it is a intrinsic element of the mystery that is being celebrated, it has not been made explicit in any form. However the liturgical tradition of the byzantine rite and of other oriental rites demonstrates itself sensible to this dimension of the celebration. In the liturgy proper to the order of the Servants of Mary, officially approved, a specific form of ritual has been found that follows right after the adoration of the Cross on Good Friday. The sober sequence of the ritual show how the Blessed Virgin Mary is indissolubly united to the work of redemption accomplished by her Son, faithful and strong unto the cross, mother of all men and women, model of the church, it is composed of a homily followed by a few moments of prayer and silence and the singing of some lines of Stábat Materor or another hymn properly chosen. In the heart of the celebration of the paschal mystery the importance of the first participation from humanity in the redeeming passion is placed discretely: as for the incarnation also for the redemption, in the sense of Col 11:24.

1) Crown of the Sorrowful Mother. Probably inspired in the use of the rosary, in the XVII century the Crown of the Sorrowful Mother was spread, initially called the Seven Sorrows. In one of the first editions printed, the Crown was composed of ritual elements that continue to be used in our days: introduction; declaration of the sorrow, one our Father – seven Hail Mary’s “in veneration to the tears shed by our Lady in her sorrows”, finally a line from the Stabat Mater (later on recited completely) with a closing prayer.

2) The Via Matris dolorosae. To facilitate the way of meditating on the sorrows of Mary, similarly to the Way of the Cross, this pious exercise remembers the sorrowful mater passing from station to station, in which each of the seven main sorrows are represented. Its origin seems to be the XVIII century and it was practiced initially and particularly in the churches of the Servants of Mary in Spain. One of the first written testimonies, conserved until today, where the method to celebrate the Via Matris is referred to in 1842. Normally these pious exercises are practiced on Fridays during lent. From 1937 until the seventies, under the form of a perpetual novena, it acquired a high importance in Chicago and in the Americas.

3) The Desolate. This pious exercise also developed in the XVIII century. It was born from the consideration that in a certain pious way, that Mary lived the climax of her suffering during the burial of her Son; in this period of time she was truly desolate; and therefore in order to show her pity some would be in prayer from late evening on Good Friday until the sixteenth hour on Holy Saturday, as well as each Friday of the year.

The image of the mother dressed in a black mantle is an almost constant presence in the popular traditions that venerate the sorrowful Mother, from the beginning of this devotion to our days. However it is not easy to find an exhaustive amount of documents that would allow the gathering of the diverse forms that popular devotion, understood in the widest sense, has expressed and continues to express its devotion to the sorrowful mother. There is no doubt that in the west the devotion to Our Lady of Sorrows, before finding it’s liturgical coding in the office of liturgy of “compassione” (from the XV century) or in the Mass (from the XV century), found a special favor in the popular expressions. The mother figure in mourning continues to be essentially tied to another pedagogically pre-dominant image, that of her standing recollected, unmoving, and silent from the Gospel of John or upon contemplating the hidden tears of the one who is standing. The same can be said of the religious expressions that developed after the council of Trent, especially in the dramatic processions and re-enactments although, not only in the south of the Italian Peninsula and in Spain. Probably today these forms, not always administered by the Christian community, are the only paper expressions that are left in popular devotion that are directly or indirectly expressed in devotion to our Lady of Sorrows.

Very recently when he was still the editor of the marian bibliography, G. Bessutti, pointed out:”The history of Christian piety with the Blessed Virgin Mary, that suffers with her Son at the foot of the cross, has not yet been written completely not only in the east, but also in the regions of the west. There is many aspects, important even, that are more or less scattered through all places and that, if they have not been ignored, at least they have not been given the due value.” In this context it refers to how in Herford (Paderborn) there was founded in 1011 an oratory dedicated to “S. Mariae ad Crucem.” This quote reveals certain interest, and in a certain way confirms the observations of Wilmart: let us place the birth of this pious trend which takes inspiration on the meditation and compassion of the Blessed Virgin Mary at the foot of the cross, before the XIII century. However, there still remains to specify the times and places that the reflections matured from the first fathers in the east and the west, the poetic and homiletic intuitions, in concrete the byzantine (for example Romanos Melodas,, that progressively placed the relation of the sword prophesized by Simeon with the compassion of the Blessed Virgin Mary and her participation in the redeeming passion of her Son.

Throughout the XIII century the devotion to our Lady of Sorrows develops, becoming more specific at the beginning of the XIV century as the devotion of the Seven Sorrow. But “the first document regarding the appearance of the liturgical feast of our Lady of Sorrows comes from a local church”; in effect, on April 22, 1423 a provincial council of Colonia issued a decree that introduced in that region the feast of Our Lady of Sorrows in reparation for the sacrilegious offenses that the hustias had committed against the images of the crucified one and of the Blessed Virgin Mary at the foot of the cross. The feast took the title of “Commemmoratio angustiae et doloribus Betae Mariae Virginis”, according to the content of the council decree that said:”… we order and establish that the commemoration of the anguish and sorrow of the Blessed Virgin Mary be celebrated every year on the Friday after the dominical Jubilate (third Sunday after Easter), unless that day another feast is celebrated, in which case it will be transferred to the following Friday”.

In the year 1482 Sixto IV composed and had it added to the Roman Missal, with the title of Our Lady of Piety, a Mass centered on the salvific event of the Blessed Virgin Mary at the foot of the cross. Afterwards that feast was spread throughout the west within diverse names and different dates. Besides the names established by the council of Colonia and that was fixed in the Mass of Sixto IV, it was called also “De transfixione seu martyrio cordis Beatae Mariae”, “De compassione Beatae Mariae Virginis”, “De lamentatione Mariae”, “De planctu Beatae Mariae”, “De spasmo atque dolorigus Mariae”, “De septem doloribus Beatae Mariae Virginis”, etc.

Mean while, on June 19, 1668 the faculty to celebrate on the third Sunday of September the "Missa de septem doloribus B.M.V.” was granted to the Servants of Maria with a formula that seems to be very similar to that of 1482. This is Mass is the one, that with some minor modifications, can be found in the missal of Pius V on Friday of the passion. In reality, the feast of Friday of the passion, granted on August 18, 1714 to the order of the Servants, and extended, by petition of the same order, to all the Latin church under the pontificate of Benedict XIII (April 22 of 1727). Also, Pius VII, on September 18, 1814 extended to the third Sunday of September the feast of the seven sorrows with the formula for the divine office and for the Mass that were already in use among the servants of Mary. Finally with the reform of Pius X, with the desire to increase the value of Sundays, this feast was set to be on September 15, date that was already in use in the ambrosian rite, that because it did not have the octave of the Nativity of the Virgin, celebrated always on that date the sorrows of Mary.

The feast of passion of Friday was reduced by the rubrics reform of 1960 to a simple commemoration. The new calendar promulgated in 1969 suppressed the commemoration of the time of the passion and reduced the category to “memorial” the feast of the seven sorrows of September under the new title of “Our Lady the Virgin of Sorrows”.

The history of this devotion, as it has been observed and as it can be deduced from these notes can trace a curved line that reaches its growth in the periods of the liturgical codification. The osmosis between the popular and the official, even amidst the recession of piety that is possible to confirm, it leads to an intense wide-spread of the feeling of devotion to the mater dolorosa. Precisely when the osmosis is at its highest point it’s when the intensity is most profound. But it is necessary to highlight the progressive liturgical consideration throughout the XX century, helped in this matter by the biblical-patristic reflection; coincides with the quality of the meditation regarding the mystery of the sorrow of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Inserting it in a wider context of salvation history; one does not contemplate or venerate the Sorrowful Mother only to consciously participate, as particular persons, in the passion of Christ in order to participate also in His resurrection, but this is also done so that Mary, as image of the church, may inspire all believers the desire to be next to the infinite crosses of men in order to bring hope, liberating presence, and redeeming cooperation. Our Lady of Sorrows can remind men and women of our time, anxious and worried about the essence of things, the confrontation with the word of truth and its manifestations certainly goes through the sword (Luke 2,35; 14, 17; 33,36; Wisdom 18,15; Ephesians 6,17; Hebrews 4,12; Revelation 1,16), that pierces the soul, but that also opens up a new conscience and a renewed mission (John 19, 25-27), that goes beyond the flesh and blood and of the will of men, since it emerges from God (John 1, 13).