I. The Crisis of Identity in the Priesthood

Almost immediately after the Second Vatican Council, a terrible identity crisis of enormous proportions began to overtake the Catholic priesthood and thousands of priests left the active ministry with or without the requisite permission. Still others became genuinely confused about the nature of their priesthood. Unfortunately, the disorientation still remains in many ways. Its causes, no doubt, are quite complex and ultimately we must confess that "An enemy has done this" (Mt. 13:28).

But recognizing a Satanic onslaught against the Lord's anointed ones does not prevent us from also seeking to discover some of the immediate contributing causes of this tragic state of affairs. In this regard Father André Feuillet makes what I believe to be some very astute observations:

Some writers claim that Vatican II is itself partly responsible. As they see it, Vatican II, in its desire to act against Roman centralization and an overemphasis on papal primacy, glossed over the problem of priesthood. In any case, it certainly intended to highlight the role of the college of bishops as successors of the Apostles. Moreover, on the basis of Scripture, it proclaimed a truth that had hitherto been too often overlooked: the sharing of all the baptized in the priesthood of Christ. By these two emphases, the Council seems to have spoken as if the bishop and the people of God were the only necessary elements of a priestly Church. In so doing, it somewhat neglected the place of the simple priest (or presbyter).

He continues by quoting from a book from D. Olivier, Les deux visages du prêtre: Les chances d'une crise:

The Council indeed maintains the special character of presbyteral priesthood as differing in essence from that of the baptized. But whereas it refers to a half dozen Scriptural texts to confirm the reality of the common priesthood, it cannot adduce a single text in favor of the famous essential difference. The contrast between the two successive passages of the Constitution on the Church is striking: the first, and very welcome one, on the priesthood of the faithful, is based on Scripture, the second is nothing but a theological development based on some texts of Pius XI and Pius XII. The bishop, who continues the mission of the Apostles, easily finds in Scripture the justification for his existence. But the priest can base his own special character only on papal statements.

Father Patrick J. Dunn, writing almost twenty years after Feuillet, comments in a remarkably similar vein:

Although the Second Vatican Council emphasizes that the common priesthood and the ministerial priesthood "differ from one another in essence and not only in degree" (Lumen Gentium 10), the nature of this distinction has not always been clearly perceived.

It may well be argued that subsequent documents of the magisterium have continued to make the necessary clarifications. The new Catechism of the Catholic Church, for instance, presents an appropriate elucidation with the following statement:

The ministerial or hierarchical priesthood of bishops and priests, and the common priesthood of all the faithful participate, 'each in its own proper way, in the one priesthood of Christ'. While being 'ordered one to another', they differ essentially. In what sense? While the common priesthood of the faithful is exercised by the unfolding of baptismal grace -- a life of faith, hope and charity, a life according to the Spirit, the ministerial priesthood is at the service of the common priesthood. It is directed at the unfolding of the baptismal grace of all Christians. The ministerial priesthood is a means by which Christ unceasingly builds up and leads his Church. For this reason it is transmitted by its own sacrament, the sacrament of Holy Orders.

While fully accepting the explanation proffered by the Catechism that "the ministerial priesthood is at the service of the common priesthood", that "it is directed at the unfolding of the baptismal grace of all Christians" and that it "is a means by which Christ unceasingly builds up and leads his Church", I am inclined to believe, with Fulton Sheen and Father Feuillet, that the concept that we have already begun to explore of the ordained minister as called to be "priest and victim" provides an insight and challenge far richer and deeper which has yet to be assimilated in the postconciliar Church's teaching and praxis.

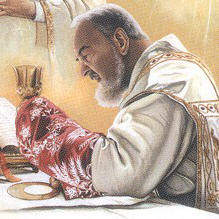

II. Padre Pio: A Model Priest and Victim

What I would like to propose further is that God has set his own seal on this explanation in the person of Padre Pio of Pietrelcina. Is it not significant that even before the great disruption of priestly life in the twentieth century was underway the Lord had already chosen Francesco Forgione to illustrate in a dramatic and extraordinary way the call to embrace victimhood in order to realize fully his vocation to the priesthood? While it is true that no one should aspire to imitate the extraordinary ways of Padre Pio without an explicit call from the Lord confirmed through wise spiritual direction and the appropriate permission when necessary, I believe that the Padre's life nonetheless constitutes a model of what it means to live as "priest and victim", a model that all Christians, but priests in particular, should strive to emulate.

Interestingly, the Trappist Father Augustine McGregor already pointed to Padre Pio as a model of priestly life over twenty years ago. In his book, The Spirituality of Padre Pio, he declared

we shall refer constantly to the priesthood of Padre Pio discovering in his life a rare model of the priestly ideal, an exemplar who revealed in a unique and simple way all the essential features of the priesthood. In short, in an age undergoing transformation in social, cultural and religious spheres we shall look for and find in Padre Pio's priesthood characteristics of permanent value, unmarked by many of today's changing values.

Even more striking, however, and totally supportive of my thesis is the testimony of Father Vincenzo Frezza with regard to the paradigmatic value of Padre Pio's priesthood. Considering how Padre Pio continually spent himself unflinchingly for souls propels him to state:

Now all of this brings us still another time to the conclusion that his vocation to the priesthood, that the fulfillment of his priestly ministry was in relation to his mission to "co-redeem." I mean that if Padre Pio had not been a priest, he could not have fulfilled his mission: priesthood and mission are identified with each other in Padre Pio. According to a poor interpretation of mine, God did not only want a new victim, but he wanted this victim to be a priest and as such placed in a priestly state like the Incarnate Word.

Here I would simply add that the last one hundred fifty years have seen the Church benefiting from what seems an unparalleled profusion of victim souls, no doubt a gift that God has given in view of the crisis which the Church is now passing through. By far almost all of these have been women and here the Lord shows us how complementary their vocation to be "co-redeemers" is to the priesthood. But, without in any way wishing to take anything away from their greatness, I would underscore with Father Frezza that in Padre Pio the Lord has done a new thing. Let us listen to him again:

Padre Pio, carrying in himself the unification of the priesthood and the mission to co-redeem, thus demonstrated that the exercise of the priestly ministry goes beyond the sacramental signs. That is, it tends to make a man "like Christ the priest" in every moment and every attitude of his existence. In simple words this means that he must become a victim, an unceasing offering. ...

Therefore, it is this state of priest-victim that colors Padre Pio's priesthood, that makes him exceptional -- I will go even further -- that makes him unique in the Church up to now. Because we meet many victim-souls in Christian spiritual history. We also know many holy priests, holy priests who took more time to say Mass and shed more tears in doing so than Padre Pio did (e.g. St. Laurence of Brindisi). We know holy priests who have made the confessional their chief ministry. We know holy priests gifted with privileged charisms. We know saints who had marked in their bodies, both in their internal and external organs, the signs of the Passion of Christ. We are astonished when faced with mystical souls who have reached the highest degree of union with God, that which we call the "mystical marriage." However, a man that summed up, that both lived and suffered all these charisms, a man that could call himself another Jesus Christ with stronger reason than that for which St. Francis was called such, up to now, only Padre Pio is such a man.

I would supplement this testimony by simply referring to the fact that Padre Pio is the first priest in the history of the Church to bear the stigmata, which, it seems, constitutes a kind of divine seal on his vocation to be a "priest-victim". Father Gerardo Di Flumeri is of the same conviction. He argues that if Padre Pio

hadn't been a priest, he would never have become a victim; priesthood and victimization in him were identical. God did not want just another victim; He wanted, instead, a new victim who was a priest, who was established in the priestly state like the Word Incarnate.

Hence I am in full accord with Father Frezza's final conclusion in this regard: "From today on, therefore, we cannot reasonably think of imagining what a priest should be if we do not compare and contrast him with Padre Pio as the model."

9III. Padre Pio's Vocation to Priest-Victimhood

Within the limits of this presentation we can only touch briefly on some of the most obvious testimony which highlights Padre Pio's vocation to priest-victimhood. Already as a young Capuchin he was beset with a host of physical afflictions which defied diagnosis.10 Later these would be coupled with demonic assaults.11 In the midst of all this it is to be noted that the young Pio was conscious of his calling to be a victim. There is clear evidence that he had fully embraced this vocation from at least the time of his priestly ordination on 10 August 1910 in Benevento.12 A remarkable confirmation of this is the fact that he had written for his own personal use the following souvenir of his priestly ordination on the day of his first solemn Mass, 14 August 1910:

O rex, dona mihi animam meam pro qua rogo et populum meum pro quo obsecro [O King, let my life be given me at my petition and my people at my request] (Esther 7:3). Souvenir of my first Mass. Jesus, my heart's desire and my life, today as I raise you up in trembling hands, in a mystery of love, may I be, with you, for the world, Way, Truth and Life, and for you a holy priest, a perfect victim. P. Pio, Capuchin.

The next evidence that we shall take into consideration is that of his letter of 29 November 1910 to his spiritual director, Padre Benedetto of San Marco in Lamis:

Now, my dear Father, I want to ask your permission for something. For some time past I have felt the need to offer myself to the Lord as a victim for poor sinners and for the souls in Purgatory.

This desire has been growing continually in my heart so that it has now become what I would call a strong passion. I have in fact made this offering to the Lord several times, beseeching him to pour out upon me the punishments prepared for sinners and for the souls in a state of purgation, even increasing them a hundredfold for me, as long as he converts and saves sinners and quickly admits to paradise the souls in Purgatory, but I should now like to make this offering to the Lord in obedience to you. It seems to me that Jesus really wants this. I am sure that you will have no difficulty in granting me this permission.

The permission was duly communicated by Padre Benedetto in a letter of 1 December 1910.15 It was also evidently prior to this time that Padre Pio first experienced the marks of the stigmata. He does not give us the exact date, but confesses in his letter to Padre Benedetto of 8 September 1911 that "this phenomenon has been repeated several times for almost a year, but for some time past it had not occurred."16 C. Bernard Ruffin indicates that already on 7 September 1910 the young Padre, ordained less than a month, went to see his parish priest in Pietrelcina and "showed him what appeared to be puncture wounds in the middle of his hands."

17In his old age Padre Pio had all but entirely forgotten about what Ruffin calls the "proto-stigmata" and then was eventually able to recall these first manifestations of the Lord's passion in his flesh.18 What I wish to underscore here is that almost immediately upon his priestly ordination Padre Pio had his first experience of the stigmata, eight years before the stigmatization of 20 September 1918 which would remain permanently imprinted upon him for fifty years. Obviously, the Lord who inspired the prayer of the young Capuchin on the day of his first solemn Mass found the petition an extremely pleasing one to which he would not delay in responding. This is also the conclusion of Father Gerardo Di Flumeri who comments on the petition which the newly ordained Padre Pio had written on the holy card on the day of his first solemn Mass:

We believe that the juxtaposition of the two words "priest" and "victim" clearly indicates that Padre Pio's offering of himself as a victim originates with his ordination to the priesthood. We believe, too, that his having received the gift of the "invisible" stigmata only a month later (Sept. 1910), indicates God's acceptance (Letters I:264f).

Hence we can say that Padre Pio's priesthood is sealed from the very beginning with the sign of victimhood. And, indeed, it is not only a sign that he willingly accepted, but even had asked for.

A. For Love of Jesus and for Souls

From this point onwards Padre Pio renews his self-offering as victim frequently and with great generosity. This offering simultaneously serves a twofold purpose; it is a fulfillment of Saint Paul's words "Now I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I complete what is lacking in Christ's afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the Church" (Col. 1:24) and it is also an act of reparation to the Lord himself. Here is how he describes it in a letter to his spiritual director, Padre Agostino of San Marco in Lamis, dated 20 September 1912:

We must hide our tears from the One who sends them, from the One who has shed tears himself and continues to shed them every day because of man's ingratitude. He chooses souls and despite my unworthiness, he has chosen mine also to help him in the tremendous task of men's salvation. The more these souls suffer without the slightest consolation, the more the sufferings of our good Jesus are alleviated.

Less than a month later he writes to Padre Agostino once again emphasizing this double objective i.e., that his victimhood is for souls and as an act of reparation to the Lord:

Believe me, dear Father, I find happiness in my afflictions. Jesus himself wants these sufferings from me, as he needs them for souls. But I ask myself what relief can I give him by my suffering?! What a destiny! Oh, to what heights has our most sweet Jesus raised my soul!

1. Victimhood for Sinners. Perhaps one of the most striking testimonies about his acceptance of victimhood for sinners is the following transcription of words taken down by Padre Agostino during an ecstasy on 3 December 1911 while the young Padre Pio was having a vision of Christ badly wounded:

My Jesus, forgive and put down that sword ... but if it must fall, let it be only on my head ... Yes, I want to be the victim ... punish me and not the others ... send me even to hell provided that I love you, and that everyone, yes everyone, be saved.

Several years later, on 17 October 1915, he writes to Father Agostino: "You exhort me to offer myself as a victim to the Lord for poor sinners. I made this offering once and I renew it several times a day."23 From this statement it would seem reasonable to conclude that Padre Pio's acceptance of his manifold sufferings always included intercession for sinners.

2. Victimhood as consolation to Jesus. Secondly, there is the note of reparation or consolation offered to Jesus. Padre Pio writes of "alleviating the sufferings of our good Jesus". This is the motive for reparation found especially in the revelations of the Lord to St. Margaret Mary who tells us that he asks for the communion of reparation to his Sacred Heart on the First Friday of the month.24 Pope Pius XI also deals with this concept in his magisterial Encyclical Miserentissimus Redemptor on the theology of reparation.

The first and obvious question that comes to mind is this: "Since Jesus is now in glory at the right hand of the Father, how can we offer him 'consolation'?" Pius XI first cited a very apposite quotation from St. Augustine: "Give me one who loves, and he will understand what I say,"25 and then gave the following reply:

If, in view of our future sins, foreseen by him, the soul of Jesus became sad unto death, there can be no doubt that by his prevision at the same time of our acts of reparation, he was in some way comforted when "there appeared to him an angel from Heaven" (Lk. 22:43) to console that Heart of his bowed down with sorrow and anguish.

In other words, as Jesus saw the sins of the world in his agony in Gethsemane by virtue of the beatific vision,27 so He also saw in advance every act of consolation offered to him until the end of time. In effect, the act of reparation which we offer now he could see then.

This second dimension, too, is notably present in Padre Pio's understanding of the reason for his sufferings. Here is an instance where he develops this motivation in a meditation on the words of Jesus in the garden of Gethsemane, "Could you not watch one hour with me?" It is fully in line with the theology of Miserentissimus Redemptor which we have just sketched above.

O Jesus, how many generous souls wounded by this complaint have kept Thee company in the Garden, sharing Thy bitterness and Thy mortal anguish ... How many hearts in the course of the centuries have responded generously to Thy invitation ... May this multitude of souls, then, in this supreme hour be a comfort to Thee, who, better than the disciples, share with Thee the distress of Thy heart, and cooperate with Thee for their own salvation and that of others. And grant that I also may be of their number, that I also may offer Thee some relief.

Not surprisingly, even in this meditation which is oriented to consoling Jesus, a reference to cooperating in our own salvation and that of others is not lacking. The two are intertwined in Padre Pio.

B. Specific Applications of Victimhood

Without taking away from the fact that he has already offered himself as a victim for sinners, for the souls in Purgatory, and in reparation, he willingly offers his innumerable physical, mental, emotional and spiritual sufferings together with the demonic assaults which he suffers for specific intentions and persons who are particularly dear to him. Thus we find him writing to his dear Padre Benedetto that

It grieves me very much to learn that you are unwell and I am praying the Lord for your recovery. As there is nothing else I can do for you, I offered myself some time ago to the Lord as a victim for you. Now that I know you are ill, I renew my offering to Jesus very often and with great fervour.

There are at least two other occasions when he reassures Padre Benedetto that he renews this offering frequently.30 He makes the same offering for his second spiritual father, Padre Agostino, with a kind of loving audacity:

Apart from everything else, you belong to me and I have every right to bargain with Jesus even unknown to you. I have offered myself to him as a victim for you and hence my behaviour cannot but be justified. What is the use of making a sacrifice if its purpose is to be frustrated?

Likewise he reassures Padre Agostino on another occasion that "I never cease, either, to present to Jesus the offering I once made to him for you."

32He makes the offering of himself in the state of victim similarly for his Capuchin Province,33 and asks Padre Benedetto for permission to do the same on behalf of aspirants for the Province.34 He also informs Padre Benedetto that he has made an offering of himself for the intention which Pope Benedict XV had recommended to the whole Church.35 It is interesting to note that all of these acts of self-oblation were made before the definitive experience of the stigmata which he received on 20 September 1918 and which marked his body for fifty years.

IV. Source of Padre Pio's Priest-Victimhood: Union with Christ

Perhaps it is not inappropriate here to ask some questions about all of these acts of making himself a victim for particular individuals or intentions. How could Padre Pio offer himself totally for more than one person or intention? In a human manner of speaking, would he not lessen the amount of merit available for a particular person or intention the more he multiplied the dedications of his victimhood? How could he multiply virtually to infinity the various purposes for which he suffered? Mathematically speaking, would he not have been reducing the effects of his suffering with every new intention which he took on?

In a real sense, of course, these questions all dissolve into mystery, but a mystery which, in effect, is based upon the infinite merits won by Christ on Calvary. Padre Pio as one man, even an extraordinarily holy man, dwindles into insignificance in the face of the woes of the world and the mystery of evil. But as priest and victim, he is united with the Eternal Priest and Victim and shares in the infinity of Jesus' merits. Let us consider Padre Pio's description of an experience which took place on 16 April 1912 after a fearful assault by the enemy:

I was hardly able to get to the divine Prisoner to say Mass. When Mass was over I remained with Jesus in thanksgiving. Oh, how sweet was the colloquy with paradise that morning! It was such that, although I want to tell you all about it, I cannot. There were things which cannot be translated into human language without losing their deep and heavenly meaning. The heart of Jesus and my own -- allow me to use the expression -- were fused. No longer were two hearts beating but only one. My own heart had disappeared, as a drop of water is lost in the ocean. Jesus was its paradise, its king. My joy was so intense and deep that I could bear no more and tears of happiness poured down my cheeks.

Yes, dear Father, man cannot understand that when paradise is poured into a heart, this afflicted, exiled, weak and mortal heart cannot bear it without weeping. I repeat that it was the joy that filled my heart which caused me to weep for so long.

This mystical experience which Padre Pio manages to describe as the "fusion" of his heart with the Sacred Heart of Jesus helps us to begin to grasp that Padre Pio's total identification with the victimhood of Jesus made him a sharer and, in a certain sense, a dispenser of those infinite merits.

V. Padre Pio's Priest-Victimhood in the Mass

While the entire earthly life of Jesus constituted a continuous offering of himself to the Father, "nevertheless the victim state of the Lord reaches the sacrificial apex at the immolation at Calvary."37 In an analogous manner we way say that, while the entire priestly life of Padre Pio was lived as a victim, nevertheless his victim state reaches the sacrificial apex at the celebration of the Mass. Let us consider these statements of Padre Pio about his Mass.

I never tire of standing so long, and could not become tired, because I am not standing, but am on the cross with Christ, suffering with Him.

The holy Mass is a sacred union of Jesus and myself. I suffer unworthily all that was suffered by Jesus who deigned to allow me to share in His great enterprise of human redemption.

Everything that Jesus suffered in His passion I suffer also, inadequately, as much as it is possible for a human being. And through no merit of mine but just out of His goodness.

39This is my only comfort, that of being associated with Jesus in the Divine Sacrifice and in the redemption of souls.

40Not only did Padre Pio experience his greatest suffering during the celebration of the Mass,41 but it was also for him the time of his most intense intercession. As on the cross Jesus could see all of us in the beatific vision,42 so Padre Pio seems to have had a similar gift. According to Father Schug, the Padre once said that

in this absorption in God, especially at the Consecration of the Mass, he saw everyone who had asked his prayers. He told his friends that they could always reach him when he was at the altar. He saw them, actually, in his gaze on God.

Again, once asked "Padre, are all the souls assisting at your Mass present to your spirit?", he answered "I see all my children at the altar, as in a looking glass."44 Indeed, because the priest is a mediator, it is his responsibility to pray for the people of God. Padre Pio took this as a solemn obligation and, even though the petitions pouring into the friary of San Giovanni Rotondo were countless, he faithfully honored every request for prayer. His intercession was -- and is still -- so powerful precisely because of his priest-victimhood. The seriousness with which he took his role as intercessor should be an admonition to every priest.

VI. Padre Pio and Priests

This brings us to a subject of capital importance: Padre Pio and priests. The Lord has confided to many victim-souls that his priests are "the apple of his eye", yet so often they are so far from fulfilling what he expects of them. Not surprisingly, very early in his state of victimhood, Padre Pio was called to make reparation for priests. Here is an account which he made to Padre Agostino, his spiritual father, on 7 April 1913.

On Friday morning [28 March 1913] while I was still in bed, Jesus appeared to me. He was in a sorry state and quite disfigured. He showed me a great multitude of priests, regular and secular, among whom were several high ecclesiastical dignitaries. Some were celebrating Mass, while others were vesting or taking off the sacred vestments.

The sight of Jesus in distress was very painful to me, so I asked him why he was suffering so much. There was no reply, but his gaze turned on those priests. Shortly afterwards, as if terrified and weary of looking at them, he withdrew his gaze. Then he raised his eyes and looked at me and to my great horror I observed two tears coursing down his cheeks. He drew back from that crowd of priests with an expression of great disgust on his face and cried out: "Butchers!" Then turning to me he said: "My son, do not think that my agony lasted three hours. No, on account of the souls who have received most from me, I shall be in agony until the end of the world. During my agony, my son, nobody should sleep. My soul goes in search of a drop of human compassion but alas, I am left alone beneath the weight of indifference. The ingratitude and the sleep of my ministers makes my agony all the more grievous.

Alas, how little they correspond to my love! What afflicts me most is that they add contempt and unbelief to their indifference. Many times I have been on the point of annihilating them, had I not been held back by the Angels and by souls who are filled with love for me. Write to your (spiritual) father and tell him what you have seen and heard from me this morning. Tell him to show your letter to Father Provincial ..."

In the annals of the mystics there are no few such plaints recorded as coming from the lips of our Redeemer. The ones from whom Christ looks most of all for consolation, particularly priests, are often precisely the ones who are the most indifferent to his loving plea for reparation. Tragically, some add contempt and unbelief to their indifference.

I believe that this vision which Padre Pio had in the early days of his priesthood was highly prophetic. If it was true in 1913, it can be verified, I believe, much more readily today. Indifference, contempt and unbelief have ravaged tens of thousands of priestly souls, unleashing an extraordinary tide of devastation upon the Church. Have we reached "high tide" yet? Only God knows and only he can respond. What is needed to turn the tide? More than anything else, I believe, are priest-victims.

When one considers the growing impact which the humble friar of the Gargano continues to have even twenty-seven years after his death, can one doubt that a legion of priests who willingly embraced victimhood, as he did, could change the face of the Church? I am convinced that there is no greater need facing the Church today.

VII. Padre Pio and Victims

You may say that I should be talking to priests and, no doubt, I should. But, I speak to you because you are here and because there is also a great need of victim-intercessors for the Church and for priests. Let us listen to a final excerpt from another letter which Padre Pio addressed to Padre Agostino just a short time before the previous letter:

Listen, my dear Father, to the justified complaints of our most sweet Jesus: "With what ingratitude is my love for men repaid! I should be less offended by them if I had loved them less. My Father does not want to bear with them any longer. I myself want to stop loving them, but ... (and here Jesus paused, sighed, then continued) but, alas! My heart is made to love! Weak and cowardly men make no effort to overcome temptation and indeed they take delight in their wickedness. The souls for whom I have a special predilection fail me when put to the test, the weak give way to discouragement and despair, while the strong are relaxing by degrees.

They leave me alone by night, alone by day in the churches. They no longer care about the Sacrament of the altar. Hardly anyone ever speaks of this sacrament and even those who do, speak alas, with great indifference and coldness.

My heart is forgotten. Nobody thinks any more of my love and I am continually grieved. For many people my house has become an amusement centre. Even my ministers, whom I have loved as the apple of my eye, who ought to console my heart brimming over with sorrow, who ought to assist me in the redemption of souls -- who would believe it? -- even by my ministers I must be treated with ingratitude and slighted. I behold, my son (here he remained silent, sobs contracted his throat and he wept secretly) many people who act hypocritically and betray me by sacrilegious communions, trampling under foot the light and strength which I give them continually ..."

Jesus continues to complain. Dear Father, how bad I feel when I see Jesus weeping! Have you experienced this too?

"My son," Jesus went on, "I need victims to calm my Father's just divine anger; renew the sacrifice of your whole self and do so without any reserve."

I have renewed the sacrifice of my life, dear Father, and if I experience some feeling of sadness, it is in the contemplation of the God of Sorrows.

If you can, try to find souls who will offer themselves to the Lord as victims for sinners. Jesus will help you.

I would compare this loving complaint of Jesus to the "great revelation" of his Heart which he made to Saint Margaret Mary in 1675,47 but what I wish to underscore here is simply the immediacy, the urgency of the call which Padre Pio heard. He answered with the sacrifice of his life. Let us take to heart these final words: "If you can, try to find souls who will offer themselves to the Lord as victims for sinners. Jesus will help you."

ABBREVIATIONS

AAS -Acta Apostolicæ Sedis (1909 -- )

Alessandro -Alessandro of Ripabottoni, Padre Pio of Pietrelcina, "everybody's cyrenean" ed. Father Alessio Parente, O.F.M. Cap. (San Giovanni Rotondo, FG: Editions "Our Lady of Grace Capuchin Friary", 1986)

Carlen 3 -Claudia Carlen, I.H.M, (ed.), The Papal Encyclicals 1903-1939 (Raleigh, N. C.: McGrath Publishing Co., "Consortium Book," 1981)

CCC -Catechism of the Catholic Church (London: Geoffrey Chapman, 1994)

D-S -Henricus Denzinger et Adolfus Schönmetzer, S.I., eds., Enchiridion Symbolorum Definitionum et Declarationum de Rebus Fidei et Morum, Editio XXXII. (Freiburg-im-Breisgau: Herder, 1963)

D'Apolito -Padre Alberto D'Apolito, Padre Pio of Pietrelcina: Memories, Experiences, Testimonials trans. Frank J. and Julia Ceravolo (San Giovanni Rotondo, FG: Editions "Padre Pio of Pietrelcina", 1986)

Di Flumeri -Father Gerardo Di Flumeri, O.F.M. Cap., The Mystery of the Cross in Padre Pio of Pietrelcina trans. Florence Di Marco (San Giovanni Rotondo, FG: Edizioni «Padre Pio da Pietrelcina», 1983)

Epistolario -Padre Pio da Pietrelcina, Epistolario a cure di Melchiorre da Pobladura e Alessandro da Ripabottoni (San Giovanni Rotondo, FG: Edizioni «Padre Pio da Pietrelcina»; Vol. I [terza ed.], 1992; Vol. II [seconda ed.], 1994; Vol. III, 1977; Vol. IV [seconda ed.], 1991)

Frezza -Father Vincenzo Frezza, O.F.M. Cap., "Priesthood and Eucharist in Padre Pio," in Gerardo Di Flumeri, O.F.M. Cap. (ed.), Acts of the First Congress of Studies on Padre Pio's Spirituality trans. Mary Brink (San Giovanni Rotondo, FG: Edizioni «Padre Pio da Pietrelcina», 1978) 347-362.

Letters -Padre Pio of Pietrelcina, Letters edited by Melchiorre of Pobladura and Alessandro of Ripabottoni; English version of Vols. I & II edited by Father Gerardo Di Flumeri, O.F.M. Cap.; English version of Vol. III edited by Father Alessio Parente, O.F.M. Cap. (San Giovanni Rotondo, FG: Editions "Voce di Padre Pio"; Vol. I, 1980; Vol. II, 1987; Vol. III, 1994)

Meditazioni -Padre Pio da Pietrelcina, Meditazioni (San Giovanni Rotondo, FG: Edizioni Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, 1991)

McGregor -Augustine McGregor, O.C.S.O., The Spirituality of Padre Pio edited by Father Alessio Parente, O.F.M Cap. (San Giovanni Rotondo, FG: Edizioni "Padre Pio da Pietrelcina", 1974)

Ruffin -C. Bernard Ruffin, Padre Pio: The True Story (Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor, Inc., 1982)

Schug -John A. Schug, Capuchin, Padre Pio (Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor, Inc., 1976)

Tarcisio -Father Tarcisio of Cervinara, O.F.M. Cap., Padre Pio's Mass edited by Father Alessio Parente, O.F.M. Cap. (San Giovanni Rotondo, FG: "Padre Pio da Pietrelcina" Editions, 1992)

TCF -J. Neuner, S.J. and J. Dupuis, S.J. (eds.), The Christian Faith in the Doctrinal Documents of the Catholic Church revised edition (New York: Alba House, 1982)

VO -François-Léon Gauthey (ed.), Vie et Oeuvres de Sainte Marguerite-Marie Alacoque, 3 vols. (Paris: Ancienne Librairie Poussielgue, 1920)

ENDNOTES

1André Feuillet, The Priesthood of Christ and His Ministers trans. Matthew J. O'Connell (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1975) 13.

2Feuillet 13-14.

3Patrick J. Dunn, Priesthood: A Re-examination of the Roman Catholic Theology of the Presbyterate (New York: Alba House, 1990) 3.

4CCC #1547.

5McGregor 62.

6Frezza 352-353 (my emphasis).

7Frezza 353-354 (emphasis mine).

8Di Flumeri 27 (emphasis mine). Cf. also Frezza 361.

9Frezza 354.

10Ruffin 62-63; Schug 29-33.

11Cf. Schug 43-56.

12Cf. Introduction in Letters I:59 [Epistolario I:48].

13Letters I:222, footnote to letter #16 [Epistolario I:196] (my emphasis); cf. Frezza 351; Alessandro 55.

14Letters I:234 [Epistolario I:206] (emphasis mine).

15Letters I:235-236 [Epistolario I:207].

16Letters I:264-265 [Epistolario I:234].

17Ruffin 69.

18Ruffin 70-71.

19Di Flumeri 24. On the term "invisible" stigimata, cf. Di Flumeri 17-18.

20Letters I:343 [Epistolario I:303-304].

21Letters I:346-347 [Epistolario I:306-307].

22Padre Agostino da San Marco in Lamis, Diario, Testimonianze, 2 a cura di Padre Gerardo Di Flumeri, (San Giovanni Rotondo, FG: Edizioni «Padre Pio da Pietrelcina», 171; quoted in Father Fernando of Riese Pio X, O.F.M. Cap., "The Mystery of the Cross in Padre Pio," in Gerardo Di Flumeri, O.F.M. Cap. (ed.), Acts of the First Congress of Studies on Padre Pio's Spirituality trans. Mary Brink (San Giovanni Rotondo, FG: Edizioni «Padre Pio da Pietrelcina», 1978) 96.

23Letters I:756 [Epistolario I:678].

24Cf. letter #86 to Mother de Saumaise of May 1688, VO II:397-398 [Letters of Saint Margaret Mary Alacoque trans. Clarence A. Herbst, S.J. (Orlando, FL: Men of the Sacred Heart, 1976) 127]; letter #133 to Father Croiset of 3 November 1689, VO II:580 [Letters 219].

25In Ioannis evangelium, tract. XXVI, 4; AAS 20 (1928) 173 [Carlen 3:325].

26AAS 20 (1928) 174; trans. in Francis Larkin, SS.CC., Understanding the Heart second, revised edition (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1980) 66.

27Cf. Arthur Burton Calkins, "The Tripartite Biblical Vision of Man: A Key to the Christian Life," Doctor Communis 43 (1990) 149-152.

28Padre Pio of Pietrelcina, O.F.M. Cap., The Agony of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane (Rockford, IL: Tan Books and Publishers, Inc., 1974) 22 [Meditazioni 64-65].

29Letters I:887 [Epistolario I:797].

30Letters I:899; 935 [Epistolario I:808; 840].

31Letters I:918 [Epistolario I:825].

32Letters I:968 [Epistolario I:869].

33Letters I:596; 607 [Epistolario I:532; 542].

34Letters I:974 [Epistolario I:874].

35Letters I:1173-1174 [Epistolario I:1053-1054].

36Letters I:308 [Epistolario I:273] (emphasis mine).

37Tarcisio 17.

38Tarcisio 21; cf. also D'Apolito 166-167.

39Tarcisio 24.

40D'Apolito 222.

41Cf. Tarcisio 34-38.

42D-S #3812 [TCF #661].

43Schug 110-111.

44Tarcisio 41.

45Letters I:395, 396 [Epistolario I:350-351] (emphasis mine).

46Letters I:385-386 [Epistolario I:342-343] (emphasis mine).

47Cf. VO II:103 [Vincent Kerns, M.S.F.S. (ed. & trans.), The Autobiography of Saint Margaret Mary (London: Darton, Longman & Todd Ltd. "Libra Book", 1979) 78].

Padre

Pio: Priest and Victim

Padre

Pio: Priest and Victim Monsignor

Arthur B. Calkins

Monsignor

Arthur B. Calkins