|

Sacred Scriptures/Liturgy- Lenten

Meditation |

Let Love be genuine

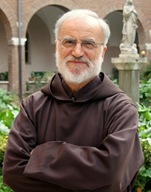

Fr. Raniero Cantalamessa, OFMCap, Pontifical Household Preacher

Third Lenten Sermon, 2011

www.zenit.org

1. You shall love your neighbor as yourself

A strange phenomenon has been observed. The river Jordan, as it flows, eventually forms two seas: the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea; but while the Sea of Galilee is teeming with life, and contains some of the most abundant fishing waters on earth, the Dead Sea is exactly that: a "dead" sea, there is no trace of life in it or around it, only saltiness. And yet it is the same water as that of the Jordan. The explanation, at least partially, is this: the Sea of Galilee receives its waters from the Jordan, but it does not keep them to itself, it lets them flow out so that they irrigate the entire Jordan valley.

The Dead Sea receives the waters and retains them for itself, it has no outlets, not a drop of water comes out of it. This is a symbol. To receive love from God, we must give it to our brothers and sisters, and the more we give, the more we receive. This is the subject of our reflections in this meditation. The water that Jesus gives us has to become "a spring inside us, welling up to eternal life" (cf. John 4:14)

Having reflected in the first two meditations on the love of God as gift, the time has now come for us to meditate on the duty to love, in particular, the duty to love our neighbor. God’s Word expresses the link between the two loves: "Since God has loved us so much, we too should love one another" (1 John 4:11).

"You shall love your neighbor as yourself" was an ancient commandment, written in the law of Moses (Leviticus 19:18) and Jesus himself quotes it as such (Luke 10:27) How than does Jesus call it "his" commandment and the "new" commandment? The answer is that, with him, the object, the subject and the reason for loving one's neighbor have all changed.

First of all the object has changed. In other words: who is the neighbor who must be loved? It is no longer only one's fellow countrymen, or at most the guest who dwells among the people, but every person, including the foreigner (the Samaritan!), even one's enemy. It is true that the second part of the phrase "You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy" (Mt 5:43) is not found literally in the Old Testament, but it does sum up the general approach expressed in the law of retaliation: "eye for eye, tooth for tooth" (Leviticus 24:20), especially if we compare it with what Jesus expects from his disciples: "But I say this to you: love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven; for he makes his sun rise on the bad as well as the good, and sends down rain on the upright and the wicked alike. For if you love those who love you, what reward can you expect? Do not even the tax collectors do as much? And if you save your greetings for your brothers, are you doing anything exceptional? Do not even the gentiles do as much?" (Matthew 5:44-47).

The subject of the love of neighbor has also changed: the word neighbor now means something else. It is not another person; it is I, it is not the person who is next to me, but the one who comes close. In the parable of the Good Samaritan Jesus shows that there is no need to wait passively for my neighbor to turn up on my path, with lights flashing and sirens blaring. There is no such thing as a ready-made neighbor; there is a neighbor when you decide to come close to that person.

And most of all, the model or measure of the love of neighbor has changed. Until Jesus came, the model was love of self: "as yourself." It has been said that God could not have chosen a more secure peg than this on which to fasten the love of neighbor. He would not have achieved the same result even if he had said: "You shall love your neighbor as you love your God!" because, when it comes to loving God, and understanding what it means to love God, a man can still cheat -- but not where love of self is concerned. We know full well what it means to love ourselves, whatever the circumstances. It is a mirror that is always before us, there is no escape.[1]

And yet there is still an escape, which is why Jesus replaces it with another model and another measure. "This is my commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you" (John 15:12). A person can love himself or herself in the wrong way, can desire evil, not good, can love vice, not virtue. If such a person loves others "as himself" and wants others to have the things he wants for himself, pity the person who is loved in that way! We know, instead, where the love of Jesus leads us: to virtue, to the good, to the Father. Whoever follows him "does not walk in darkness." He has loved us by giving his life for us, while we were still sinners, in other words, enemies (Romans 5:6 ff).

We can now understand what the evangelist John means by his apparently contradictory statement: "My dear friends, this is not a new commandment I am writing to you, but an old commandment that you have had from the beginning; the old commandment is the message which you have heard. Yet in another way I am writing a new commandment for you" (1 John 2:7-8). The commandment of the love of neighbor is "old" in the letter, but "new" with the novelty of the Gospel itself -- because it is no longer just a "law" but also and first of all a "grace." It is founded on communion with Christ, made possible by the gift of the Spirit.[2]

With Jesus there is a move from a two-person relationship: "What the other person does to you, do the same to him," to a three-person relationship: "What God has done to you, do the same to the other person," or, starting from the opposite direction: "What you have done to others is what God will do to you." There are countless sayings of Jesus and the Apostles which repeat this concept: “As God has forgiven you, so you are to forgive one another": "If you do not forgive your enemies from the heart, neither will your Father forgive you." Our excuse is cut off at the root: “But he does not love me, he offends me." That's his business, not yours. The only thing that concerns you is what you do to others and how you behave in face of what others do to you.

But the main question still remains to be answered: why this singular diversion of love from God to one's neighbor? Wouldn't it be more logical to expect: "As I have loved you, so you must love me," rather than: "As I have loved you, so must you love one another"? Here is the difference between love that is purely eros and love which is eros and agape together. Purely erotic love is a closed circle: "Love me, Alfredo, love me as much as I love you": thus sings Violetta in Verdi's Traviata: I love you, you love me. The love of agape is an open circle: it comes from God and returns to Him, but passes through one’s neighbor. Jesus himself inaugurated this new kind of love: "As the Father has loved me, so have I loved you" (John 15:9).

St. Catherine of Siena gave the simplest and most convincing explanation of the reason for this. She puts these words into God's mouth: "I ask you to love me with the same love with which I love you. But this you cannot do for me, because I have loved you without being loved. All the love you have for me is a love of debt, not of grace, in as much as you are obliged to do it, while I love you with the love of grace, not of debt. Hence, you cannot give me the love that I require. Because of this I have placed your neighbor alongside you: so that you may do to him what you cannot do for me, that is, love him without considering whether he deserves it, and without expecting anything in return. And I consider as done to me what you did to him."[3]

2. Love one another with a sincere heart

After these general reflections on the commandment to love our neighbor, the time has come to speak of the quality this love must have. It is essentially two-fold: it must be a sincere and active love, a love of the heart and a love, so to speak, of the hands. This time we pause on the first quality, under the guidance of that great singer of love, Paul. The second part of the Letter to the Romans is a whole succession of recommendations about mutual love within the Christian community: "Let love be genuine [...]; love one another with brotherly affection; outdo one another in showing respect" (Romans 12:9 ff). "Owe no-one anything, except to love one another; for he who loves his neighbor has fulfilled the law" (Romans 13:8).

In order to grasp the spirit that unites all these recommendations, the underlying idea, or rather the "feel" that Paul has for charity, one must start with the initial word: "Let love be genuine!" It is not just one of many exhortations, but the matrix from which all the others derive. It contains the secret of charity. With the help of the Holy Spirit, let us try to grasp that secret.

The original term used by St. Paul, translated as "genuine," is anhypokritos, namely, without hypocrisy. This word is a sort of pilot light; it is, in fact, a rare term that we find used in the New Testament almost exclusively to describe Christian love. The expression "genuine love" (anhypokritos) returns again in 2 Corinthians 6:6 and in 1 Peter 1:22. This last text enables us to grasp the meaning of the term in question with complete certainty, because he explains it in different words; genuine love -- he says -- consists in loving one another intensely "from the heart."

Hence, with that simple affirmation -- "Let love be genuine!" -- St. Paul takes the discussion to the very root of charity, to the heart. What is required of love is that it be true, authentic, not a pretence. Just as wine, to be "genuine," must be squeezed from the grape, so must love come from the heart. In this, too, the Apostle is the faithful echo of Jesus' thought; in fact, repeatedly and forcefully, the Lord pointed to the heart as the "place" where the value of what a person does is decided, and what is pure or impure in the life of a person (Matthew 15:19).

We can speak of a Pauline intuition with regard to charity: behind the visible and exterior universe of charity, made up of works and words, he has revealed another, wholly interior, universe, which is, in comparison with the first, what the soul is to the body. We find this intuition again in the other great text on charity, which is 1 Corinthians 13. When you look closely you see that what St. Paul says there refers entirely to this interior charity, to the dispositions and the sentiments of charity: charity is patient, it is kind, not jealous, not angry, it bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things. There is nothing here, specifically and directly, about doing good, or works of charity, but everything is taken back to the root of wanting that which is good. Benevolence, wanting what is good, comes before doing good.

The Apostle himself is explicit about the difference between the two spheres of charity when he says that the greatest act of exterior charity -- distributing all one’s goods to the poor -- would be of no use at all without interior charity (cf. 1 Corinthians 13:3). It would be the opposite of "genuine" charity. Hypocritical charity, in fact, is precisely that which does good, but without willing the good, which shows something externally that does not have a corresponding "attitude" in the heart. In this case, there is an appearance of charity which may even be a mask for egoism, self-seeking, using another person, or simply the remorse of conscience.

It would be a fatal error to see charity of the heart and charity in deed as being opposed to one another, or to use interior charity as a kind of alibi for a lack of active charity. In any case, to say that without charity “it does me no good at all” even if I give everything away to the poor, does not mean to say that it does no good to anyone and is useless. Rather, it means that it does no good “to me”, but it might help the poor person who receives it. So, it is not a question of lessening the importance of charitable works (we will look at this next time), but of ensuring that they have a firm foundation against selfishness and its infinitely wily ways. St. Paul wants Christians to be "rooted and grounded in love" (Ephesians 3:17); in other words, love has to be the root and foundation of everything.

To love genuinely means to love at a depth where you can no longer lie, because you are alone before yourself, alone before the mirror of your conscience, under the gaze of God. "He loves his brother," writes Augustine, "who, before God, where God alone sees, reassures his heart and asks himself deep down whether he really acts thus out of love for his brother; and his witness is that eye which penetrates the heart, where man cannot look."[4] That is why Paul's love for the Jews was genuine if he could say: "I am speaking the truth in Christ, I am not lying; my conscience bears me witness in the Holy Spirit, that I have great sorrow and unceasing anguish in my heart. For I could wish that I myself were accursed and cut off from Christ for the sake of my brethren, my kinsmen by race" (Romans 9:1-3).

To be genuine, Christian charity must therefore begin from within, from the heart; the works of mercy must spring from "heartfelt compassion" (Colossians 3:12). However, we must make it clear at once that this is something much more radical than mere "internalization," that is, more than a shift of emphasis from the external practice of charity to the interior practice. That is only the first step. Internalization leads to divinization! The Christian, as St. Peter said, is one who loves "with a genuine heart": but with which heart? With "the new heart and the new Spirit" received in Baptism!

When a Christian loves like that, it is God who loves through him; he becomes a channel of God's love. Something similar happens with consolation, which is nothing other than a way of manifesting love: "God comforts us in all our sorrows, so that we can offer others, in their sorrows, the consolation we ourselves have received from God" (2 Corinthians 1:4). We console with the consolation by which we are consoled by God, we love with the love with which God loves us. Not with a different love. This explains the apparently disproportionate effect even a very simple act of love can sometimes have, even oftentimes a hidden one, in terms of the hope and light it can create.

3. Charity edifies

When charity is mentioned in the apostolic writings, it is never spoken of in the abstract, in a generic way. The background is always the building up of the Christian community. In other words, the first sphere of the exercise of charity must be the Church and more specifically the community in which one lives, the people one relates to each day. This is how it should be also today, especially at the heart of the Church, among those who work in close contact with the Supreme Pontiff.

In ancient times it was customary for a while to apply the term 'charity', agape, not only to the fraternal meal that Christians shared together, but also to the whole Church.[5] The martyr St. Ignatius of Antioch greets the Church of Rome as the one "that presides over the charity (agape)," that is, over the "Christian fraternity," over all the Churches.[6] This phrase affirms not just the fact of the primacy, but also its nature, or the way of exercising it, namely, in charity.

The Church is in urgent need of an outburst of charity which will heal her fractures. In one of his addresses Paul VI said: "The Church needs to feel the wave of love flowing once more through all her human faculties, that love which is called charity and has been poured into our hearts by the Holy Spirit that has been given to us."[7] Love alone heals. It is the oil of the Samaritan. Oil also because it must float above everything else, as oil does in relation to liquids. "And over all these put on love, which binds everything together in perfect harmony" (Colossians 3:14). Over everything, super omnia!! Hence also over discipline, over authority, even though, obviously, discipline and authority can be expressions of charity.

One important area on which we need to work is that of mutual judgments. Paul wrote to the Romans: "Why do you pass judgment on your brother? Or you, why do you despise your brother? ... Let us stop passing judgment on one another" (Romans 14:10.13). Before him Jesus had said: "Do not judge, and you will not be not judged. [...] Why do you see the speck that is in your brother's eye, but do not notice the log that is in your own?" (Matthew 7:1-3). He compares the neighbor’s sin (the sin judged), no matter what it is, to a speck, compared to the sin of the one who judges (the sin of judging), which is a beam. The beam is the very fact of judging, so grave is it in the eyes of God.

The discussion on judgments is certainly delicate and complex and it cannot be left half-finished if it is not to appear immediately unrealistic. How can anyone live without judging at all? Judgment is implicit in us, even by a look. It is impossible to observe, to hear, to live, without making assessments, in other words, without judging. A parent, a superior, a confessor, a judge, whoever has a responsibility over others, must judge. Sometimes, in fact, as is the case of many here in the Curia, judgment is, precisely, the type of service that one is called to give to society or to the Church.

In fact, it is not so much the judgment we must remove from our heart, but the poison from our judgment! That is, the resentment, the condemnation. In Luke's account, Jesus' command "Do not judge, and you will not be judged" is immediately followed, as if to make the meaning explicit, by the command: "do not condemn, and you will not be condemned yourselves" (Luke 6:37). In itself, judgment is a neutral action, the judgment can end either in condemnation or absolution or justification. It is negative judgment that is taken up again and banished by the word of God, the judgment that condemns the sinner as well as the sin, that is aimed more at the punishment than the correction of a brother.

Another qualifying point of sincere charity is esteem: "Outdo one another in showing respect for one another" (Romans 12:10). To esteem one's brother, one must not esteem oneself too much, not be always sure of oneself; as the Apostle says "no-one should exaggerate his real importance" (Romans 12:3). Whoever has too high an idea of himself is like a man who, at night, has before his eyes a source of intense light: he can see nothing beyond it; he cannot see the lights of his brothers and sisters, their merits and values.

"To minimize" should become our favorite verb in relations with others: to minimize our own merits and the defects of others. Not to minimize our defects and the merits of others as we often tend to do, which would be the exact opposite! There is a fable of Aesop in this connection, as reworked by La Fontaine, which goes like this:

"When coming into this valley

each carries on his back

a double knapsack.

Inside the front one

willingly he stuffs the faults of others,

and in the other puts his own." [8]

We must simply reverse things: put our own faults in the knapsack in front of us, and the faults of others in the one behind.

St. James warns: "Do not slander one other"(James 4:11). Today, slander has a different name: it's called gossip and seems to have become an innocent thing, but in fact it is one of the things that most pollutes our lives together. It is not enough to avoid speaking ill of others, we must also prevent people from doing so in our presence, making it clear, perhaps by our silence, that we do not approve. How different the atmosphere is in a workplace or community where St. James's warning is taken seriously! In many public places there used to be a notice saying: "No smoking here" or even: "No blaspheming here." It would be a good idea in some cases to replace them with "No gossiping here!"

We finish by listening to the Apostle's exhortation to the community of the Philippians, as though his words were addressed to us: "Make my joy complete by being of the same mind, one in love, one in heart and one in mind. Do nothing out of jealousy or vanity. Instead, out of humility of mind, everyone should give preference to others, everyone pursuing not his own interests but those of others. Make your own the mind of Christ Jesus" (Philippians 2:2-5).

NOTES

[1] Cf. S. Kierkegaard, "Gli atti dell'amore," (Works of Love) Milan, 1983, p. 163.

[2] J. Ratzinger -- Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth Part II, Ignatius Press, San Francisco, 2011.

[3] St. Catherine of Siena, Dialogue 64.

[4] St. Augustine, Homilies on the First Epistle of John, 6, 2 (PL 35, 2020).

[5] Lampe, A Patristic Greek Lexicon, Oxford 1961, p. 8.

[6] St. Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Romans, initial greeting.

[7] Address at the General Audience of Nov. 29, 1972 (Insegnamenti di Paolo VI,Tipografia Poliglotta Vaticana, X, pp. 1210 f.).

[8] J. de La Fontaine, Fables I, 7.

[Translation by ZENIT]

Return to Lenten Sermons Page - by Fr. Rainero Cantalamessa...

This page is the work of the Servants of the Pierced Hearts of Jesus and

Mary